Alexandra Leonard ’09 heals and builds community, one tile at a time.

By Fran Czuk

A series of ceramic casts of heads and bodies, a short story, and a documentary film served as senior year course work and a Senior Integrated Project, as well as the beginning of self-created art therapy after a traumatic year for Alexandra Leonard ’09.

Art proved a way of beginning to process, heal, connect and build community for Leonard after a time in her life when everything seemed to fall apart. Now she is helping her community heal from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and rebuild as they participate in the creation and installation of mosaic tiles in her grant-funded project in downtown Lansing, Michigan.

A native of Mason, Michigan, Leonard grew up hearing about Kalamazoo College from her father, David Leonard ’71. She chose K for its small size and integrated study abroad program. Her study abroad experience in Nairobi, Kenya, was a turning point in her life.

“It was the best and worst experience of my life,” Leonard said. “The first five months were everything you want from study abroad—cultural immersion, living with a great host family.”

Then, after the December 2007 presidential election in Kenya, accusations of vote rigging erupted into two months of violent protests, police use of excessive force, ethnic-based killings and reprisals that left more than 1,000 dead and up to 500,000 people displaced, according to Human Rights Watch.

“We were in lockdown for a month, couldn’t leave the apartment,” Leonard said. “At one point, we had to shut the windows because tear gas was coming in. I lived close to downtown, across from a park where protests turned violent. I was watching this place I’d fallen in love with crumble.”

Before the election crisis, Leonard had taken a class at the University of Nairobi. “The professor told us to watch this election carefully based on what we’d learned about the history of Africa and colonialism. He said, ‘You walk around and this looks like a peaceful country. But Kenya is a sleeping lion and you will see how this comes out and everything is just under the surface.’ Then it was so much worse than people were anticipating.”

While the political events unfolding around her engulfed Leonard in shock, at the same time she learned that a childhood best friend had died violently under mysterious circumstances.

“To this day, they don’t really know what happened to her and the facts between sources vary,” Leonard said. “I realized death is much harder to process when you don’t actually know what happened.”

By the time Leonard returned home, she found her other childhood friends had moved past the desire to talk about her friend, further isolating her as she struggled to share her experiences in Africa.

“I didn’t know a lot about therapy or PTSD back then,” Leonard said. “I didn’t realize I was dissociating a lot to cope. I hardly felt any emotion and I thought, ‘I guess this is how I am now.’”

Leonard found some relief in art. For her SIP, she created eight ceramic casts of the heads and bodies of human models. Each piece featured a viewing portal to various materials and scenes Leonard had arranged inside. Her SIP title, Things Fall Apart, referenced the well-known novel about the effects of colonialism in Africa by Nigerian author Chinua Achebe, her feeling that her own world had fallen apart, and the reality of working with ceramics, which can fail, break or explode in the kiln.

The night before her SIP exhibit opened, Leonard was in the Light Fine Arts Building setting up. Across the room, behind her back, one of the heads suddenly fell and smashed on the floor.

“It had been sitting there for two hours, and I thought, ‘This would happen. I named the thing Things Fall Apart; did I make that happen somehow?’ It was terrible at the time, but now I consider it a bit of a spiritual experience—probably partially from sleep deprivation.”

Leonard stayed up all night epoxying the sculpture together. “I was thinking about ancient Greek sculptures and how little shards are always missing, and that’s what that one looks like now,” Leonard said. “I love it, actually, a lot more than I did before.”

Her SIP also included a short story she wrote for English Professor Emerita Gail Griffin’s creative nonfiction class.

“I wrote out the story of the Kenya saga in different flashbacks juxtaposed with what my friend was like, what I wanted to remember about her, what we knew happened,” Leonard said. “It gave some language to the deep feelings I couldn’t speak.”

Simultaneously, Leonard found more healing in making a film about her friend for a documentary filmmaking class.

“I interviewed her mom and a number of close friends, and I had that time talking about her that I had never gotten,” Leonard said. “To me, that was all I could do to hang on to her, while also trying to let go. I’d spend all day editing video and feel like I had spent the whole day with her. It was really beautiful. That’s grieving.

“I think I beat myself up for a long time about my grief and how long it felt like it was taking. I had some very kind professors at K who were understanding of the fact that it was hard for me to talk about and yet I wanted to talk about it, too.”

After graduating with a degree in art, Leonard needed a break. She moved to the Lansing area, working first in the hospitality industry and on her family’s farm, then in financial planning with her father, while participating with Sunset Clay Studio in Lansing. She traveled extensively around the country and the world with a focus on art. In 2018, a uniquely high-ceilinged gallery space spurred the creation of a 200-section hanging sculpture which she then entered into arts competition ArtPrize in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

“It was about 10 years after my experience in Kenya and the first time I’d done body casting work since my SIP,” Leonard said. “I had a lot more of my feelings processed in healthier ways. That sculpture was about my friend, and a tribute and an honor to the ways we grieve, the ways we process our feelings, and the ways our trauma houses itself in parts of our bodies. It was a hard journey to make. For me, I want to not block my mind from those things. I also don’t want to keep reliving it over and over.”

Now, Leonard works sometimes in the restaurant industry, currently for The People’s Kitchen, and in custom residential tile work with Heritage Flooring. Owner and lead tile installer Paul Torok has served as a mentor, teaching her about tiling and encouraging her artistic involvement in mosaic tile projects.

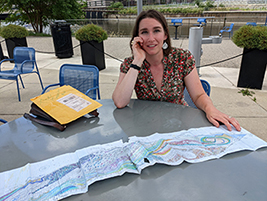

Since 2020, her time and energy have been devoted to the Shiawassee Street Mosaic Project.

The community art installation on the wall of the Shiawassee Street Bridge in downtown Lansing’s Rotary Park brings Leonard back to a trajectory she began her sophomore year at K, when she delved into community organizing with a community-based sociology course connected to Building Blocks, a nonprofit organization that empowers residents to enhance the quality of life in their own neighborhoods.

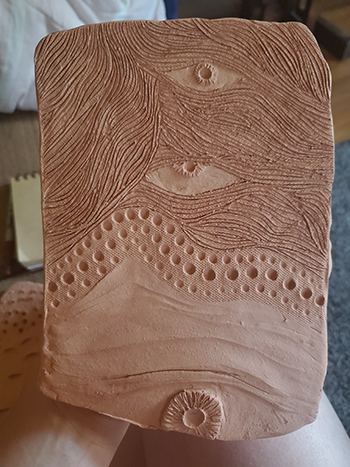

The 650-square-foot mosaic on the Lansing River Trail features tiles made, glazed and installed by more than 2,000 community members during many workshops orchestrated by Leonard in venues all over the city. Funded by a $75,000 City of Lansing Arts Impact Project Grant, the mosaic was originally intended to be a six-month project in 2020. However, the impacts of COVID-19 and the reality of the multi-step process extended the project another two years.

One of her favorite parts of the project has been engaging people who do not consider themselves artists and did not initially want to participate.

“A couple would come up and one person would be really into making a tile and the other person is just waiting for them, or a dad might be waiting for his kids to make tiles,” Leonard said. “I’d just put a tile in front of them, and tell them, it doesn’t have to be a masterpiece; they all look beautiful when they get glazed.”

The tiles tell thousands of stories. One section serves as a memorial for a good friend of Leonard’s who died in July 2021 and includes both tiles made by the friend and tiles inspired by her, crafted at a memorial workshop.

“This is my rough-and-ready master plan, my treasure map,” Leonard said. “Once I got the grant, I put together this now very beat-up and scaled rough draft on graph paper. I’ve been inspired by the James Webb Space Telescope sending back photos. There’s a big awesome swirl that was inspired by Jupiter. It’s now come to mean a lot of other things to me.”

“That brought me back to when I was working on my SIP, where that was art therapy for me and I could pour myself into the work and speak things in nonverbal ways,” Leonard said. “When people have told me stories about their tiles, it’s often in memory of people they love, and that to me is such a beautiful thing.”

In the future, Leonard plans to tend and touch up the mosaic as needed. She also intentionally designed it to allow for the possibility of expanding the mosaic. In addition, she is interested in expanding her technical tilesetting and mosaic skills as well as returning to more sculptural art.

Leonard loves that ceramics is both an ancient and impermanent art form.

“Ceramics can be artifacts that teach us about humans thousands of years ago. We uncover mosaics that are pristine under dirt and rubble. And yet, you can crash your sculpture on the ground, and then this piece you’ve poured yourself into is ruined. You take your precious artwork, and load it in a 2,000-degree oven where, who knows what’s going to happen to it? I’ve had sculptures explode in the kiln and you open it and there’s just dust left.

“I hang on to things so hard. And I love ceramics as a practice of surrender. When something breaks of mine, it has to be fine. I can’t do anything about it. I put a tile up one day when it was 85 degrees out and sunny and our mud was drying so quickly. It was this beautiful tree with individual leaves and everything. And five minutes later, it fell off and broke into five pieces. Well, this is life; things fall apart. We puzzle it out and put it back together as best we can.”

The Process: From Bags of Clay to Community Mosaic

Professor, Advisor, Mentor

Arcus Social Justice Leadership Professor of Art Sarah Lindley was Alexandra Leonard’s academic advisor at Kalamazoo College. Leonard reflects on how she came to major in art and the role Lindley played in her development:

When I initially started at K, I thought I was going to major in anthropology and sociology or in psychology. My sophomore year, I wasn’t too pleased about having to pick a major because I was enjoying the well-roundedness of taking all kinds of subjects.

At the time, I was taking a pottery 101 course, intro to wheel throwing. I was really enjoying this class, and I had an epiphany in the studio, where I realized, I can see myself not ever getting sick of this. Art seems all-encompassing to me. Anything I’m interested in pursuing, I can fit into art.

Sarah [Lindley] was my advisor. I took a number of courses with her and worked as a student intern for her in the summers. She would work on her own art, and I would work alongside her. As a professor, she was pretty tough. In the summer, when we were working one on one, it was a more relaxed feeling.

She was my first introduction to true ceramics work, and she is very methodical in her approach. We would do a lot of preliminary research on the topic and make a lot of drawings that evolved into patterns. We would make small models of the work that were going to be scaled up much larger.

She taught me to have rules when I’m working on art. She would often introduce assignments in parts. She’d give you a part, such as, come to class with a bunch of repeating objects. Then the next class, she’d throw something else in there, like, now you have to assemble them and here are the rules about what you can and can’t do in assembling them. It could be really maddening when you were getting a vision, and she would throw you for a loop with, “It can’t be symmetrical,” or something. She said when you leave things open ended, it doesn’t push you as much to create better art.

I realized in community tile workshops, when I created a little bit of structure, a shape to the tile instead of abstract pieces, or a one-sentence prompt, people seemed to have an easier time and it did yield better tiles overall.

I set up my studio very similarly to the way Sarah’s studio at her house was set up when I worked with her. I do a lot of research. I am pretty methodical, but I do like there to be some spontaneity. I have a plan, but I always leave room for imperfection, because ceramics always has surprises.

Unpredictable things can still happen despite all your best-laid plans. It’s almost a spiritual thing for me to surrender a piece to the kiln and say, I’ll hopefully see you later.