by Sarah Frink

“I’m Jason, and welcome to Grobbel’s, America’s oldest and largest corned beef specialist since 1883.”

That’s how Jason Grobbel ’84 introduces himself to new employees of E.W. Grobbel Sons, Inc., at the company’s monthly training meetings. The company was established by his great-grandfather; Grobbel bought out other family interests in the company in 1988 and helped build it from a small regional processor with sales of $4 million, to a nationally distributed processor with sales of over $110 million annually. Today he serves as the company president, uniting his talent for business with his passion for developing people.

In that monthly training meeting, Grobbel makes the company priorities clear.

“We’ve gotten here because we are a great company,” he tells his employees. “And we are a great company for two big reasons: The people in this room are great players. Yet players don’t make a great company just because they’re great individually. Something has to bring those players together—and it has to be a noble mission. We’re here to grow and develop each other both personally and professionally, and on the side, we make great food products!”

E.W. Grobbel Sons, Inc. was founded by Emil Wilhelm Grobbel, a young immigrant who came to America near the turn of the 20th century from the Westphalia region of Germany. At first, Emil worked for a meat company in the original Eastern Market in Detroit, Michigan. When the owner died the next year, Grobbel says, “There was an Irishman by the name of Fitzpatrick who operated the slaughterhouse down by the river. He convinced my great-grandfather to go into business for himself, because he was one of the few bilingual German immigrants, and he could help Fitzpatrick sell meats to other German sausage makers.” They started a business relationship, and eventually, Emil’s son, Grobbel’s grandfather, married Fitzpatrick’s daughter. Grobbel’s father also married an Irish woman. “We were specialty meats early on, but perhaps that’s why we focused in on corned beef—most people hear a German name like Grobbel and think we’d be in the sausage business. But that’s how we evolved.”

Grobbel didn’t always picture himself at the helm of his family’s four-generation business. He was the sixth of eight children born to hard-working parents. After Grobbel was born, his mother went to law school, becoming a prosecuting attorney, and then a municipal judge in Grosse Pointe before serving as a probate judge in Macomb County. She encouraged Grobbel to follow in her footsteps and study law, yet Grobbel felt more inclined toward architecture, even dreaming about attending the School of Architecture at Taliesin for graduate school. He started his college career at Michigan State, but found it wasn’t for him. He transferred to K, where he ultimately majored in business administration. He found he had a passion for advertising, and he did his Senior Individualized Project in marketing. “I still love the psychology of it,” he says. “I took a number of psych classes at K, even though I didn’t major in it.”

His K-Plan included study abroad in Spain and he developed a lifelong love of international travel. He’s enjoyed sharing that love with his family. “I’ve taken all five of my kids to Germany and Ireland,” he says, including daughter Samantha, who graduated from K in 2011 with a degree in fine arts. “Kalamazoo was amazing,” he says. “I felt it was a peaceful place. It helped me tremendously to figure out who I was, and the K-Plan, all those experiences, pushed me to where I am today.”

Instead of pursuing a career internship—then a common component of the K-Plan—Grobbel essentially interned at the family business. “At that point, while I was still thinking of going in a different direction, I kept getting pulled into the company, because there were a lot of struggles.”

Grobbel’s father was leading the business at that time. “My parents, unfortunately, went through a painful divorce in the mid-80s. So right after I graduated, I went from the frying pan into the fire, trying to help pull the business together. We were in financial distress, and by 1988, we had been working with a turnaround guy. We realized that either we had to let it go and walk away, or somebody had to carry it forward.” So, at the age of 26, Grobbel became the sole owner.

There were roughly 25 employees at the company when Grobbel took over. Today there are about 250 core employees, with that number rising to 350-450 during corned beef season, which runs about six months out of the year. They ship out close to 25 million pounds of corned beef annually, deploying over 350 semi loads across the country in the weeks leading up to St. Patrick’s Day. “It’s a logistical ballet,” Grobbel says. “We build up inventory in our freezers and then begin shipping out mid-February. Probably 35% of our sales are in the first quarter.” Grobbel’s provides corned beef to every state in the country and they are the exclusive supplier to Walmart and Sam’s Club. The company also produces other quality meats like roast beef, pastrami and prime rib, and they continue to diversify their products.

“People ask me, ‘Four generations in a family business—how is that possible?’ And I say, it’s sheer dumb luck.”

Finding someone in the family who has both the business acumen and the drive to carry the business forward is rare, he says.

“Everybody blames the failures of a family business on the second or third generation, but it’s usually the first generation—expecting that your children should take over just because they’re the fruit of your loins is not a solid business plan. When I speak in front of small business operators who have started thinking about succession planning, I find they don’t believe they can bring in a young professional who is not a family member, even though non-family-owned businesses do this all the time. Those businesses find people who have the abilities and the passion. But family businesses somehow get in a mindset where they think that that’s impossible. You can have a business that’s family-owned and professionally led.”

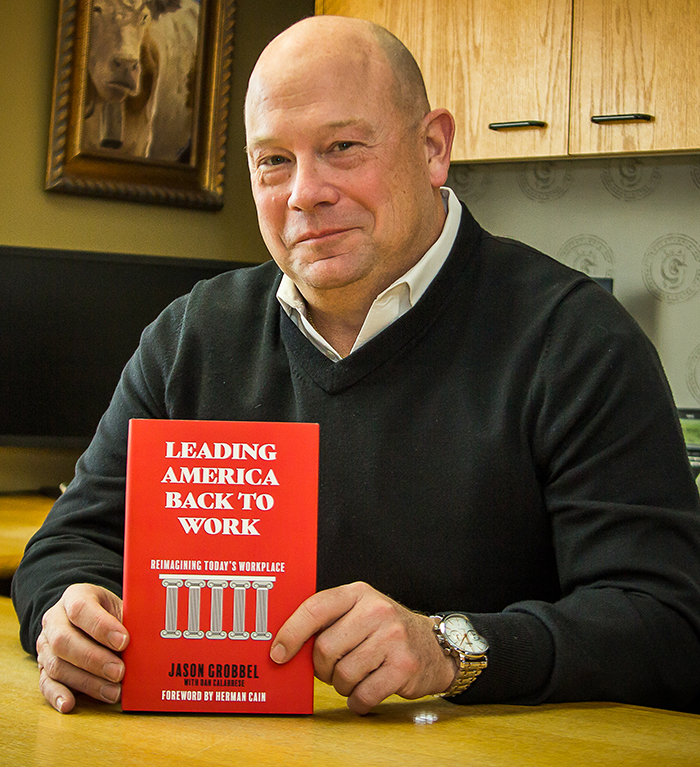

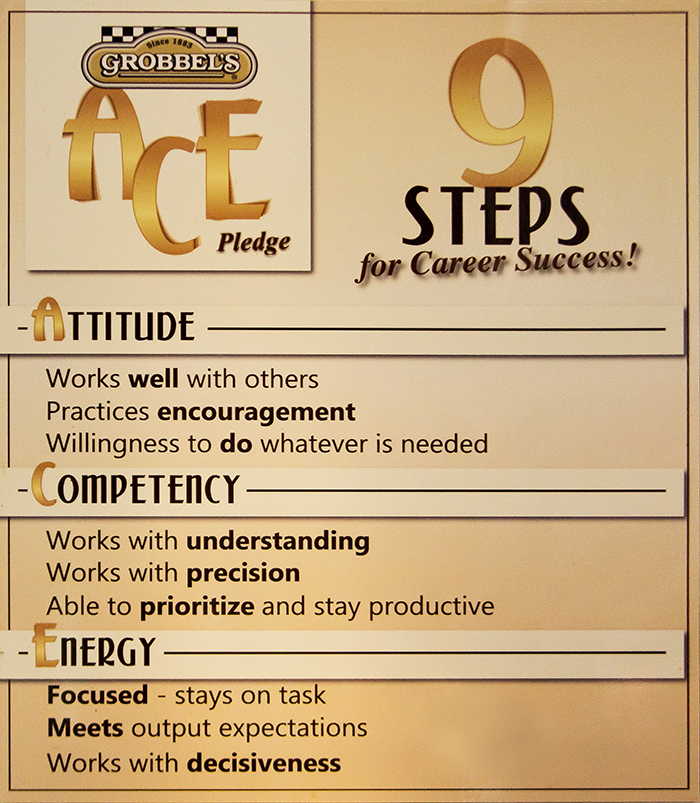

As for Grobbel, he believes in hiring the right talent, and for him, the right talent doesn’t mean the “elusive unicorn” who comes in fully equipped with the knowledge and skills for the job. His focus is on creating systems that put new hires in a position to learn and succeed, and where the workers can envision their own success. To this end, the company has developed a human resource system over time that they call ACE. ACE is based on the three words that Grobbel believes are the key to unlocking job growth and productivity: Attitude, Competency and Energy. He is so passionate about this system that it’s the basis of a book he’s written, titled Leading America Back to Work: Reimagining Today’s Workplace.

The system is supported by five pillars. The first is recruitment and cultural fit—a fit for the company’s culture, and a fit for the task that will be performed. The second pillar is onboarding and engagement. At Grobbel’s, new employees spend the first week working half days, giving them a chance to job shadow experienced employees and acclimate physically to the work environment. Next is supervision and leadership. Grobbel notes that not every technical expert makes a great people manager, and this is a pitfall many companies face when they hire and promote. His company hires personnel managers who support technical supervisors with the fourth pillar, which is evaluation and guidance. Employees meet with their personnel manager once a month for a regular check-in, and this supervisor evaluates employees weekly on their ACE scores. If scores dip, a meeting is scheduled right away to help the employee get back on track.

The final pillar under ACE is process evolution and task fragmentation. By specializing in one fragmented step of the manufacturing process, the employee can become proficient and productive at that task and make it their own. For example, a person with little experience could come in and be trained on trimming beef briskets. Within three weeks, that person could be proficient at their job and feel like a contributing member of the team. Over time, the company provides opportunities to learn new tasks even as they focus on their assigned task, positioning them for change or growth.

“We hear politicians and people say there’s a skills gap. I say they’re wrong. There’s no skills gap in the employees. The skills gap is in the employers.”

He explains, “Henry Ford, over 100 years ago, transformed automobile manufacturing, and he brought farmhands from the South on board with no skill or knowledge. Yet on Day One, working for him, they were 20 times more productive than a master mechanic, doing it in a completely different way. So not only did he take 20 times the manhours out of the process, but those manhours didn’t require a lifetime of education to be effective. So, by reinventing what we do, and the way we do it, we can adapt to the workers of today and help them to become productive.”

Underpinning the whole system is a culture of respect among employees that his organization works deliberately to maintain. In his book, Grobbel writes, “One principle to get you started is that you don’t respond to anger with anger, or to disrespect with more disrespect….When you’re always uplifting and positive with your words, you will win the day….What we’re doing is teaching an entire company full of people how to treat each other like this, and how to enjoy the benefits of doing so.” The approach taken by leadership is critical to establishing the dignity of work, which leads to satisfaction in work, which can lead to a fulfilling sense of purpose for employees and more stable and productive workforce for employers.

This is the sweet spot for Grobbel. He asserts that people who have become disengaged from the workforce can find the joy of being part of a great team that cares about them and can feel what they do matters, if workplaces can adapt to their needs and show workers they are connected to the mission.

“The seemingly most mundane or menial job is vitally important to the company’s noble mission. Each and every one,” Grobbel says. “Our vocations are the core of ourselves, and we have to understand the beauty in work. And how God gave us all gifts—all very different.”

Reflecting on his own vocation, Grobbel says, “I am proud that we have a team of great people who care about each other, who are really trying to embrace this concept of our collective purpose here, which is to help each other grow both personally and professionally.

“That never gets boring,” he says. “It gets me up every day. Watching people grow and develop is the greatest honor and the greatest joy I could ever have.”

That, and making some great corned beef on the side.![]()

Grobbels Gives Back

In April, amid the pandemic outbreak, Grobbel’s donated 40,000 pounds of corned beef brisket and hash to Forgotten Harvest, an organization that delivers food to pantries and agencies that serve metro Detroit families in need.