A New Fellowship in Learning

By Sarah Frink

As a Kalamazoo College senior and aspiring journalist, Bob Sherbin ’79 had set his career sights on becoming a foreign correspondent in Africa. When the opportunity arose to apply for a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship—a one-year grant for purposeful, independent exploration outside the United States, awarded to graduating seniors nominated by one of the fellowship’s partner institutions—Sherbin applied, hoping the experience would bring him one step closer to his goals. He was awarded the coveted fellowship. His project, which carried him along the red washboard-like dirt roads of West Africa among long-distance truck drivers, would prove the most formative experience of his life—a gift that he hopes to pay forward through a new fellowship he is establishing at Kalamazoo College.

Sherbin grew up in the suburbs of Detroit. While most of his peers were heading off to college at Michigan State or University of Michigan, Sherbin said, “Socially, that felt a lot like heading off to 13th grade with really great sports. I was looking for something more intimate and individualized, with room for exploration.” Kalamazoo College—with its K-Plan, its gold-standard study abroad program and the LandSea pre-orientation program—spoke to Sherbin’s longing for adventure.

He came to K committed to becoming an oceanographer. “I loved watching Jacques Cousteau documentaries and was a competitive swimmer, so I thought I could marry those two interests,” Sherbin said. Then, one fateful Monday morning, he walked into Professor Herb Bogart’s experimental fiction freshman seminar. “It was love at first sight,” Sherbin says. “I was absolutely staggered, entranced with English and with Professor Bogart. There were 15 or so freshmen in that seminar and probably half became English majors. It was that good.”

His ambitions rerouted, Sherbin recalls taking classes and pulling all-nighters with his then roommate and fellow English major Jerry Root ’79, cranking out papers on their Smith Corona typewriters to the tunes of Taj Mahal and Bob Marley. He became involved with The Index, eventually becoming co-editor. “I started doing it in earnest my junior year,” Sherbin said. “There was a guy editing it, John Hitchcock ’78, who was kind of the Ben Bradlee of The Index. He was a year older than me and also wanted to be a foreign correspondent.” Hitchcock would become a valued friend and connection throughout Sherbin’s life.

For career service, he went to Washington, D.C., bunking with Doug Doetsch ’79, who became another lifelong friend, but Sherbin really had his eye on study abroad. He wanted to get as far away from the familiar as possible. There was a program in Sierra Leone that interested him, but anti-government demonstrations were occurring throughout the country and the program was cancelled at the last minute. Instead, he attended the University of Nairobi—the only K student there that year, and one of only six American students. Among the academic highlights was studying African literature with teacher Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, who is regarded today as one of Africa’s greatest living writers and a contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature. While in Nairobi, Sherbin scheduled classes to allow for four-day weekends. “I’d go hitchhiking almost every weekend, which was less insane at the time than it sounds, either on my own or with a friend. We’d go wherever the cars were going. I spent many hours in the back of pickup trucks, sitting on burlap bags of coffee and freshly picked tea, looking out at the Rift Valley, wondering what I was going to do with my life.”

When he returned to K, he knew he wanted to spend more time in Africa, perhaps becoming a journalist there, and thought about how he could do that. He met with Bill Pruitt, a mentor who ran the African Studies program. It was Pruitt who helped Sherbin conceptualize and shape his proposal to apply for the Watson Program. “My proposal was to study the sociology of long-distance truck drivers in West Africa. The reality was that I had never been to West Africa and I’d never taken a sociology class, but I wanted to look at how truck drivers could serve as a model for understanding the development of African society at the time. I got the grant, and was thrilled. A friend came up to me the next day and said, ‘Are you sure you really want to do this?’ I thought, maybe this is going to be more challenging than I thought. But I decided I’d just figure it out as I went along.”

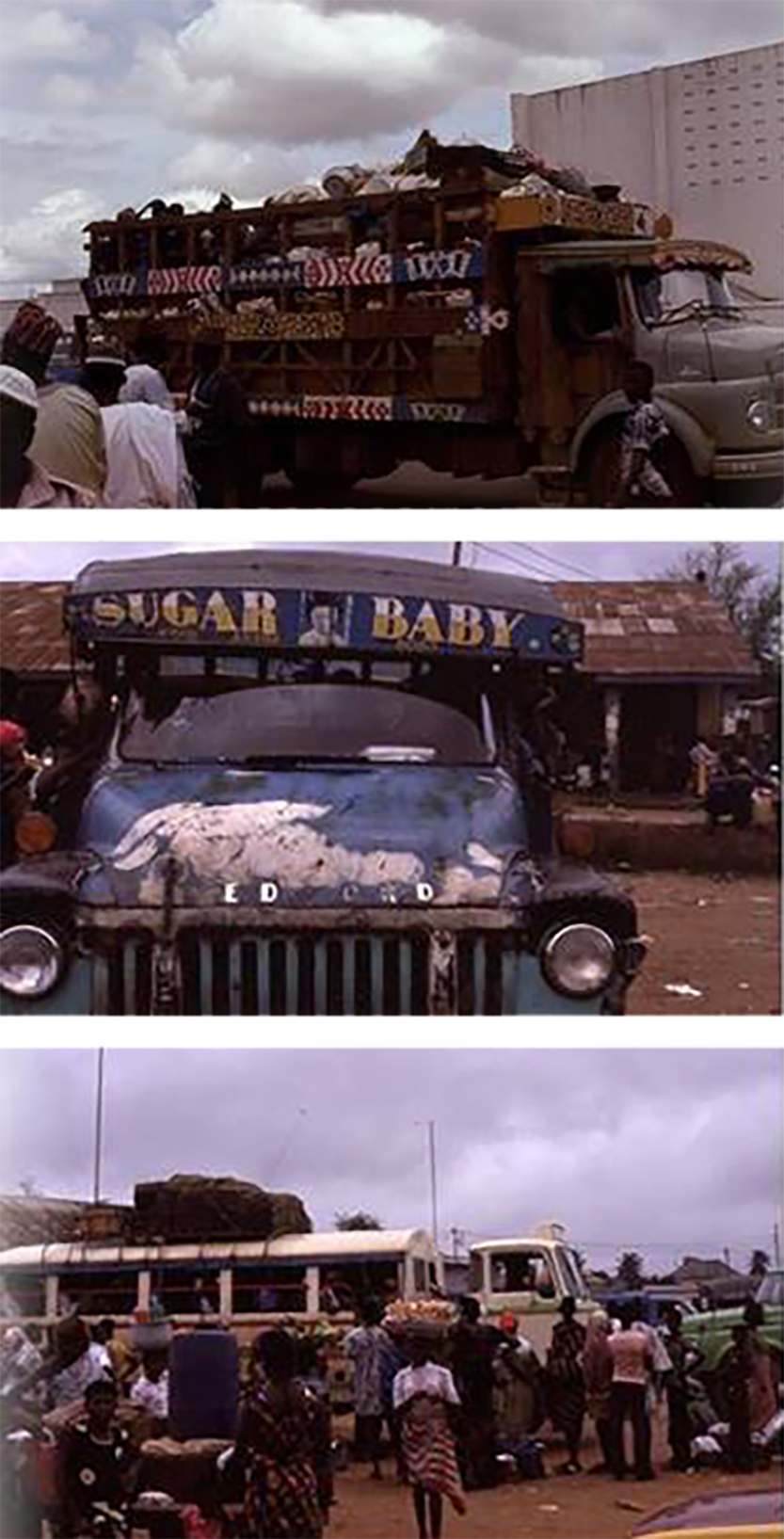

Sherbin spent the next year in Africa, thousands of miles from anyone he knew, at a time before cell phones or WhatsApp to keep in touch. He was on the road about half the time, living mainly with Peace Corps volunteers. “I based myself in a village in Cameroon, then the capital city of the Central African Republic, Bangui, and a town in central Ghana and made forays from there. These were trucks taking people rather than cargo—there weren’t really buses and there certainly wasn’t domestic air travel, so that was how people got around, and they moved their lives with them,” he said. “I focused on things like apprenticeship rituals, how the drivers used juju to protect themselves, and the kinds of naming conventions that were associated with cars. Drivers were small-time capitalists who lived in communal villages, and I studied how they balanced those things. It was the most extraordinary year—I got to know all sorts of people. I got involved in a few accidents—there was no AAA along the red roads of Africa—and got thrown into jail as a suspected CIA agent.” The fellowship showed Sherbin that he was able to “fumble my way forward and figure out how to put the pieces together” to create a structure for learning not only more about Africa, but more about himself. “The thing about the Watson was, I was a decent enough student—I had a lot of passion, but I don’t know that I had the most glowing academic record. Yet the Watson Fellowship invests in individuals and kind of makes a bet on them, and I felt that I owed it to them to do a good job on the project since they had taken a bet on me.”

After a year of travel, Sherbin came back to the States tired and noticeably scrawnier than when he had left. He applied to graduate schools in journalism and literature, thinking he’d take whichever program started later, to take more time to recuperate. (“That was the extent of my career planning,” he joked.) His friend from The Index, John Hitchcock, had gone on to Northwestern and their program started in late September, so Sherbin followed suit and soon graduated, a freshly minted journalist amidst a newspaper recession. Finding a job was a challenge. He got an offer in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, with a little help from Hitchcock, who put in a good word for him at his employer.

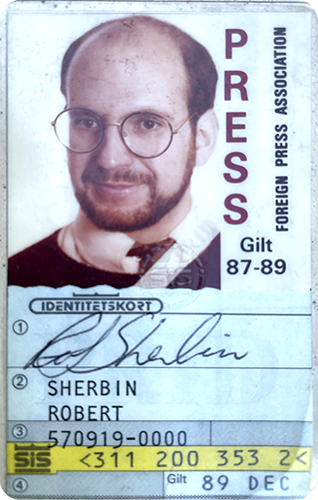

He started out as the night police beat reporter, and after two years was the senior feature writer. Sherbin still had the desire to become a foreign correspondent, and so he went on to Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in Washington, covering Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union through an American lens. It wasn’t taking him where he wanted to go, however. Hitchcock had gone on to AP Dow Jones—a joint venture of the Associated Press and the Wall Street Journal. He helped Sherbin meet the right people there, and they told him that within two years he would be sent as a correspondent overseas. “I thought this might be the way to get back to Africa, or—since I spoke French—maybe to a French-speaking part of the world,” Sherbin said. “One day, the phone call came and they said, ‘Can you get to Stockholm in three weeks?’”

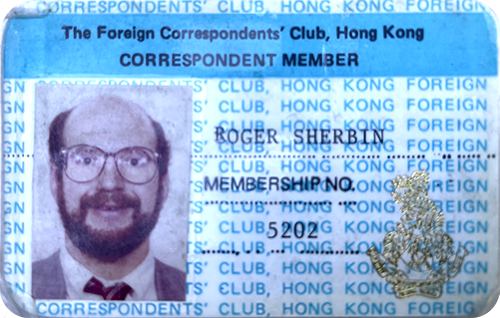

Ever the adventurer, he was soon on a plane bound for Stockholm, where he covered the Nordic region and tried to learn Swedish. After two years there, he went back briefly to New York, and then to Hong Kong—another place he’d never expected to be. He and his wife, Mollie, whom he’d met during his time in Pennsylvania, moved into a tiny apartment with just a mattress, expecting to stay for six months. It looked, he said, “like a communist safehouse.” He spent four years covering southern China. When they told him they wanted to move him to Eastern Europe, he knew he wanted to stay in Asia, so Sherbin reached out to the largest company he was covering at the time, Hongkong Shanghai Bank (now HSBC), and got a job running investor relations.

Having transitioned from journalism to corporate communications, Sherbin moved on to another local company before switching to tech, working for PC maker Gateway—which some may remember as the computer company with the cow-spotted boxes. “The idea of selling cow-spotted boxes in India was such a unique challenge, I thought that would be the place to go.” He ran marketing and communication there until the tech bubble burst—and then went to a similar role at Merrill Lynch. Two years in, Sherbin was on a business trip in Mumbai, India, when his phone rang in the middle of the night—it was New York, letting him know he’d been laid off. Sherbin recalls, “I was walking through the wet markets of Mumbai, thinking, what on earth am I going to do? I’ve got three young kids and very expensive rent in Hong Kong…and then my cell phone rang.” It was Gateway. Two hours after being laid off from Merrill Lynch, he had an offer to come back to Gateway in the States.

With that fortuitous turn of events, the family relocated to San Diego, and from there to Silicon Valley, where he joined Hewlett Packard as vice president of corporate communications. Looking for something “smaller and edgier,” Sherbin went to a company called NVIDIA in Santa Clara, where he continues to serve as VP of corporate communications. “At the time I started at NVIDIA, it was a small computer graphics company,” Sherbin said. “With some really farsighted leadership, it’s grown to become one of the biggest tech companies in the world.”

Which brings Sherbin to present day, and the philanthropic idea that had been percolating in his mind. “During COVID, I thought a lot about what I was grateful for and what helped shape my life. I realized I owed a real debt to Kalamazoo College and some of my mentors and friends there. I was aware that the College was no longer a partner institution with the Watson. I thought it would be really cool to create something like that for K students, so they would have a similar opportunity.” Sherbin’s father had passed away a few years prior, and he said, “I thought it would also be a great way to honor him and the encouragement he always gave me. He shared with us a love of travel and the emphasis that the important part of travel isn’t the sites you see but the people you meet along the way. It gave us the confidence to do things that were out of the ordinary.”

This past spring, Sherbin established the Jerry Sherbin Fellowship, which will provide one K senior with a stipend to pursue an academic year post-graduation, independently exploring a subject of deep personal interest outside the United States. Applicants will be assessed based on their proposal’s creativity and personal significance, their passion for the subject, and how the work may shape their future plans. By design, the fellowship is more an investment in the applicant’s future than a recognition of outstanding academic achievement, though it is anticipated that candidates will have a strong record of success at K. The first fellowship will be awarded to a senior in 2023. The recipient will be expected to travel back to K the fall following their project’s conclusion to share their experience with others, inspire the next graduating class, and form a connection with future recipients that may grow into a virtual community.

Sherbin said, “It’s my hope that the fellowship will enable students to widen their perspectives, taking them from DeWaters to Da Nang, from the Upjohn Library steps to the Russian steppes and beyond, before they head into the rest of their lives. I hope that it will be given to individuals who may not know exactly what they want to do and who will benefit from the time and space to figure it out. When making this gift, I thought, these are such crazy times—there might be more pressing causes I could give to, but in the longer run, maybe the individuals who receive this fellowship will be able to make a real difference in ways that we can’t anticipate. There are people out there who maybe deserve to be bet on.” Just as his mentors at K and the Watson Foundation once made a bet on Bob Sherbin.