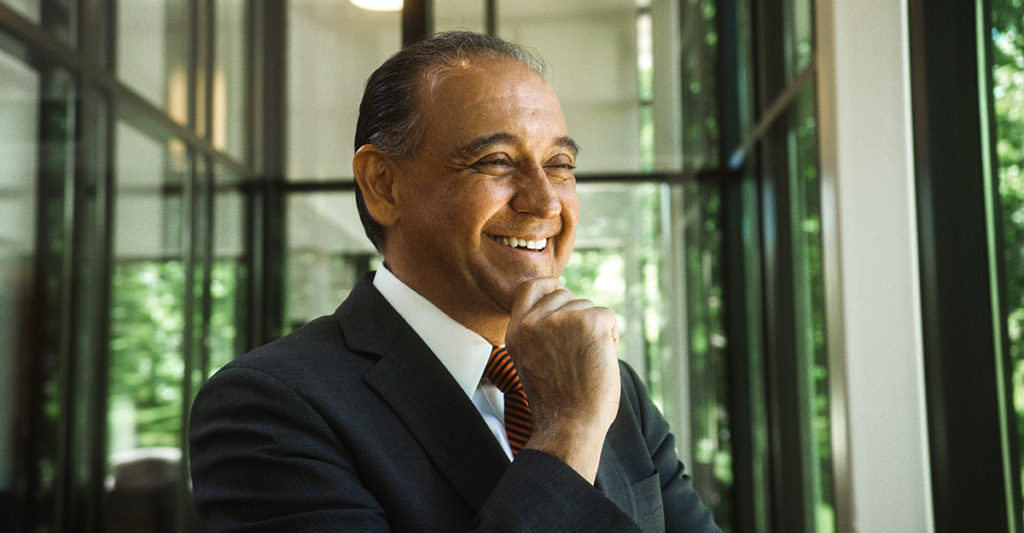

By Fran Czuk

When Tim Meier ’78 lived in Trowbridge Hall, just to the right of the stone etched, “The end of learning is gracious living,” he had a very particular vision of what gracious living meant to him at that time: “A veranda overlooking a body of water and having somebody on staff bring me fancy drinks.”

Meier acknowledges that this is not how his life turned out, and yet, “what I’ve found is that gracious can mean filled with grace. I’ve found a lot of grace in being able to witness, to accompany, to laugh with, and to cry with folks who would otherwise not have someone there.”

Supported by mindful self-care, that grace—along with other lessons learned at Kalamazoo College—has carried Meier through earning graduate degrees in philosophy, immunology, theology and molecular neuroscience as well as becoming a Jesuit priest, working in biological research, joining the military, and serving as a chaplain in a children’s hospital. He has studied the body and brain and journeyed alongside soldiers traumatized by war and families grieving sickness and death, all without losing his faith or his sense of humor.

Along the way, Meier has sung for a pope, played piano in a neuroscience lab, taught college students and organized weekend retreats for recovering addicts.

In conversation, Meier is dryly humorous and self-deprecating, full of entertaining stories, and matter-of-fact about his complicated history with alcohol and his tendency to distract himself with long tangents.

His email signature offers a glimpse into his many accomplishments: S.J., Ph.D., M.A., M.S., M.Div., Th.M.; Former Chaplain (Major), U.S. Army, California Army National Guard; The Order of California (2018).

Yet when asked how he prefers to be identified, Meier said, “At some point, people started calling me either Doctor Father or Father Doctor Tim. When I joined the military at 51, I decided, I’m Captain Doctor Father Tim. Then when I got promoted to major, I didn’t like the way Major Doctor Father Tim sounded, so I kept the captain. When I was in the army, people would call me Chaplain or Chappie. At the hospital, I’m usually addressed as Father Tim.

“But mostly, I’m just Tim.”

Meier first considered joining the Roman Catholic religious order the Society of Jesus when he was in high school at the University of Detroit Jesuit High School and Academy. A Jesuit teacher there advised him to go to college first—if he had a vocation, it would wait.

So, in summer 1974, Meier headed across the state to Kalamazoo College for a two-week orientation program. He had always loved science, and he planned to major in biology, his favorite subject area. Participants selected three possible areas of study for the orientation, and Meier chose math, history and music.

“It turns out that (Professor of Music) Russ Hammar took anybody who had put music in any spot, and he made a little orchestra and chorus to perform Mozart’s Misericordias Domini,” Meier said. “In two weeks, we were able to put this together and have a little concert, and I found that I really liked doing music. It hit me that if I could also major in music, I didn’t want to look back 40 years down the road and say, ’Oh, I wish I had done that.’ I don’t have the talent to make music my life’s work, but I knew that music was in my soul.”

Tim Meier ’78 recalled that as a student, “I gave my senior recital the first Monday of senior quarter. I invited the whole campus. I put a little invite in everybody’s box in the mail and my piano professor got really mad, because about 40 minutes before showtime, the recital hall was filled, and people were still coming. He said, ‘What is this?’ I told him, ‘Oh, I invited everybody on campus.’ He said, ‘But we’re going to have to do this in the theatre. You’ve not practiced in the theatre!’ He went into conniptions, but lot of people showed up, and I had a great party afterward.”

Meier appreciates that Kalamazoo College was a place where he could double major, study abroad in Spain, perform independent study in biblical Greek, and audit German classes simply because he was interested.

“I am so glad that I was able to major in music and in biology, and I think Kalamazoo College was one of the few places where I could get a really good education in both. I’m grateful that was not just a possibility, but that it became my reality.”

During study abroad, Meier began to get serious about the call he felt to the priesthood. When he returned, he contacted the Jesuits without telling any of his family or friends. Upon graduation, he received offers for a Heyl Graduate Fellowship to Yale (available to K graduates in certain fields) to study pharmacology, a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship to study orchids in Colombia and Venezuela, and an invitation to the Jesuit order.

“I told my parents that I was going to become a Jesuit, and my dad said, ‘Don’t you think you should go to Yale first?’” Meier said. “It was an option, but I opted not to.”

On September 3, 1978, Meier joined the Jesuits. The formation of a Jesuit priest encompasses five stages and can last more than 15 years. For Meier, the process would span almost 30 years.

First, he spent two years in the Novitiate stage, learning about community, ministry, the Society of Jesus and Ignatian spirituality and making a 30-day silent retreat, the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola, before pronouncing vows of poverty, chastity and obedience.

For the second stage, First Studies, Jesuits at that time studied philosophy for two years. Meier enrolled in the Jesuit philosophy program at Loyola University Chicago, taking piano lessons at Mundelein College and singing countertenor each Sunday in the Episcopal Church a few blocks south of campus (the rest of the choristers sang in the Lyric Opera Chorus).

“I had never had philosophy as a course while I was at Kalamazoo College, so here I am doing a master’s degree in something I had never studied before,” Meier said.

The third stage of Jesuit formation, Regency, involves active ministry, often teaching. Meier wanted to teach biology, and in order to do so, his next step was to attend Georgetown University as a student, where he earned a master’s degree in immunology. He then taught biology for three years at John Carroll University in Cleveland.

The fourth stage, Theology Studies, is a final step toward priestly ordination. Meier proceeded from John Carroll to the Jesuit School of Theology in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he earned both a Master of Divinity and a Master of Theology. While earning the second degree, Meier—who has been clean and sober since 1979—began assisting another Jesuit in giving weekend retreats to people in 12-step programs. He wrote a thesis reflecting on that experience, titled “Toward a Theology of Recovery from Addiction.”

Meier still wasn’t finished with his formal education. From Cambridge, he headed to Stanford University in California, where he intended to continue his study of immunology. Once he arrived, however, “There wasn’t anything going on there in immunology that caught my fancy.

“I heard this guy give one of the best lectures I’d ever heard, so I went to visit him, and from down the hall, I could see a studio upright piano in his lab. I decided, upon seeing the piano, I don’t care what this guy does, I need to work with him. And it turned out that he was doing molecular neuroscience, something I had not done. It was a fabulous experience in his lab.”

At the end of his second year at Stanford, Meier also organized a recital of biologists in music at Stanford, which started small, with 30 or so people, but grew quickly, with a crowd of more than 300 by the time of the sixth recital in the fall of Meier’s fifth year.

“We had spectacular music, and it was really, really fun, until the chair of my department, who was also on my doctoral thesis committee, put a kibosh to it,” Meier said. “He said, ‘You’re spending too much time doing that, not enough time doing your degree.’ I don’t know about the too much, but it’s true I was not rushing the degree because I knew I would have to go back to the Midwest, and I was really enjoying living in a place where some flowers bloom outside all year round. It took me seven years to finish my doctorate.”

After a year of post-doctoral work at Stanford, Meier taught biology at Xavier University in Cincinnati, where he was able to take voice lessons and gave his first voice recital since college.

In 2002, Meier returned to Stanford as undergraduate research coordinator and director of the honors program in biological sciences.

“That was my dream job,” Meier said. “I was able to keep doing some research, I did some teaching, and I did administration—which is not my idea of a great thing to be doing, but it enabled me to do the other things. I was back in California, and I got to interact with amazing folks. It was fun that several of the folks in the department were unsettled by the fact that I am professionally religious, except they couldn’t gainsay my credentials to be there, because they had given me those credentials.”

While working at Stanford, Meier started the last phase of Jesuit formation, Tertianship, in 2005. (While Jesuits typically start this year of reflection and discernment about five years after ordination, Meier had been ordained 14 years prior.) A significant piece of Tertianship entails making the Spiritual Exercises again in another 30-day silent retreat.

“Much to my horror, in the midst of that silent retreat, it became clear to me that I was supposed to join the U.S. military,” Meier said. “I’m old enough to have had a draft number for Vietnam, which was really unsettling, despite the fact that by the time I got my draft number, the draft was effectively over. Still, I had wanted nothing whatsoever to do with the military, except that, in the summer of 2005, this comes up.”

The call to service, Meier said, was incontestable.

“January of 2006, I actually wind up meeting with military chaplain recruiters. Then October 2006, all of a sudden, I’m G.I. Tim, and I had been accepted into the U.S. Army as a captain in the Chaplain Corps. No one was more surprised than me to find that going on.”

Meier spent June through August of 2007 in basic training at age 51.

“It was not my idea of a really good time,” Meier said. “Doing pushups on fire ant hills at five in the morning was not how I imagined my golden years were going to begin.”

In June 2008, Meier embarked on the first of four overseas deployments.

“I had a lot of reservations about joining the military; one of them was that I ‘have more degrees than a rectal thermometer,’ according to a friend whom I had trusted (at least up to that point),” Meier said. “I was afraid that would be a bar against junior enlisted personnel in particular being able to derive benefit from my being around. Ironically, junior enlisted got along with me really well. It was the officers who had trouble with the fact that I had so much education. I know a little about a lot of things—and I really am grateful to Kalamazoo College for nurturing that in me.”

In fact, Meier found he could lean on his molecular neurobiology knowledge to help service members understand what happens in the human brain in situations of stress and trauma. It also helped him develop coping strategies for himself, particularly to manage the traumatic stress of deployment and the 189 helicopter missions he went on.

“Not only do I not like war movies, I really don’t like roller coasters,” Meier said. “Too often, the aircraft would start doing—let’s say acrobatics. A couple of times, I learned after the fact that the acrobatics were the crew trying to get Chappie to barf. Other times they weren’t. And I found that, as this thing is doing its bucking bronco imitation, if I could force myself to take just three mindful breaths in a row, I could feel a teeny tiny bit less stress. The more I forced myself to breathe in through the nose and out through the mouth slowly, it felt better for me.”

As everyone in the helicopters wore ear protection, and Meier was not usually connected to the intercom system, he found that he could sing without anyone hearing him, and that also helped him get through difficult flights.

“I made up a little ditty that I would sing based on the words from one of the songs that I sang at my senior recital at Kalamazoo College, Green Pastures. It’s kind of a riff on the 23rd Psalm, the Lord is my shepherd sort of thing. That helped a lot, too.”

On one mission in Iraq, Meier noticed a helicopter pilot “in the Darth Vader helmet” had a purple stuffed Beanie Baby attached to his uniform. “I just thought that was the best thing; it was so incongruous. I did not think I could get away with a purple Beanie Baby, but I wondered if I could find one that would be less immediately discernible.”

At the time, the Army was regularly confiscating stuffed animals because they were being used to disguise improvised explosive devices, so bags of them sat in the chaplain’s office.

“I went and emptied this box out on to a big table—there had to be 100 of them there,” Meier said. “I saw Mr. Bear, who was sort of brownish tan. I began putting him in one of the pockets on the body armor that I was wearing. Several noncommissioned officers would get a little aggravated, like, ‘I’m sure that’s not authorized.’ My response would be ‘Oh, thank you, sergeant,’ and I would just keep doing it. A lot of the junior enlisted soldiers thought that my having Mr. Bear was really funny. On my next three deployments, I decided to take him with me. I was never ordered not to have him with me, and I liked having him around.”

Meier turned 60 on his fourth and final deployment, which ended in 2016. He worked for the State Military Department, overseeing chaplains from the Army National Guard, Air National Guard and California state militia, until April 2018. As Meier accompanied service members and veterans on their journeys from trauma toward healing, while simultaneously working to process his own experiences, he began to see how gracious living could mean offering grace to yourself and others.

From there, Meier moved to Los Angeles, where he helped at a Jesuit parish on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood for a few months before being assigned to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles as a chaplain in June 2019.

As the only Roman Catholic priest at one of the top pediatric facilities in the country, Meier was called on frequently to minister to families with extremely sick children.

“I meet families at some of the most difficult times they might ever have,” Meier said. “I’m really aware that Messiah is not part of my job. I physically cannot effect positive change in this situation. I cannot heal the child. I can’t take on or take away anybody’s pain. But what I’ve learned is, I’m good at accompanying people through at least part of this journey. I’m grateful that I have had the opportunity to journey with these folks.”

Sometimes an old friend did the journeying with Meier.

“I’ll bring Mr. Bear around, and I’ll show the child pictures from deployment and mention that Mr. Bear didn’t really like flying on aircraft, but I liked having him with me,” Meier said. “I tell them that if Mr. Bear got scared, he would pull the cover of the pouch he was riding in over his head so he could hide, and he’d feel safer, and he’d still be with me, so I’d feel safe, too. The kids and even their parents seem to think that’s funny.”

At the hospital, Meier leaned on his K experiences in a way he never saw coming. His year in Spain, which had no direct connection to what he was studying, brought him to a point of fluency in Spanish that—with some work to re-establish proficiency—has helped him communicate with families whose primary language is Spanish.

“I’m really grateful that Kalamazoo College set me up—in a good way— for something I never would have imagined I would be drawing on 45 years later.”

There are good days and bad days at Children’s Hospital, times of grief and loss that brought Meier back to the trauma and powerlessness of deployment as well as “some spectacular, indescribably wonderful, joyful outcomes.

“Recently, there was a patient on the palliative care list and everybody was convinced this patient was at death’s door. Now it looks like the patient may go home this week. And everybody’s baffled except for the patient’s mom, who really believes that this was a miracle. There are wonderful outcomes and there are some that are really, really sad. I find it fraught because it takes a lot of psychic and spiritual energy for me to be able to detach with love and recognize that I can’t make things better. Working at the hospital takes a lot of emotional intentionality and a lot of self-care on my part.”

The mindful breathing he practiced on Black Hawk helicopters is an essential part of Meier’s self-care.

“When I was in grad school, if the concept of mindfulness came up, the received wisdom among neuroscientists was that these people are claiming really spectacular benefits, and they must have a screw loose,” Meier said. “But since I left Stanford, there’s been a lot of research published in really excellent peer-reviewed journals indicating the benefits of simply breathing mindfully. It doesn’t need any sort of meditation component or religious or spiritual context; just the breathing itself leads to statistically significant drops in the levels of circulating glucocorticoids, which was, ironically, what most of the people in my lab at Stanford were looking at.

“Mindfulness has been a really important component of my program of self-care and of spiritual exercise, if you will. And that helps me to be able to go to work and be present to folks who need someone maybe just to be there in silence.”

In silence—and in grace. Always, for Meier, from the Kalamazoo campus, through classrooms and research labs, on the battlefield, to hospital rooms echoing with grief or joy, he finds and shares that grace with others.

And as for his own next chapter? The future is somewhat uncertain. During a recent medical evaluation of his traumatic stress injuries, Meier was surprised to receive a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Additionally, he was encouraged to leave employment at Children’s Hospital since the many stressors there were aggravating prior traumatic stress injuries. Whatever lies ahead for Meier, however, he is sure to lean on grace. As he has journeyed alongside so many others through difficulty and struggle, he now embarks on his own next journey with a lifetime of truly gracious living to accompany him.

“I am grateful beyond words for my time at Kalamazoo College, for the rich educational challenges and opportunities, and for lifelong friendships and satisfying memories. I continue to pray in thanksgiving, daily, for everyone associated with Kalamazoo College.”

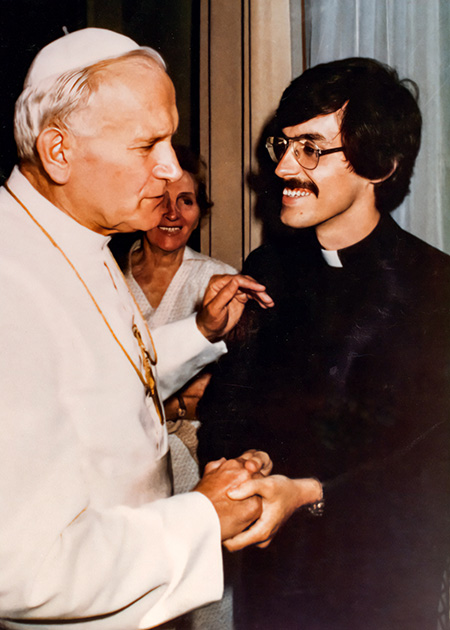

Singing for the Pope

In 1982, Tim Meier ’78 spent a summer living in the Jesuit Community of the Papal Palace at Castel Gandolfo in Italy, headquarters of the Vatican Observatory, studying late-type red giant stars.

“At night I would go into the central spiral staircase of this palace that had been built in the 16th century and sing,” Meier said. “The acoustics were fabulous.”

One evening, a chance encounter with two young people who stopped to listen to Meier singing led to a connection with their grandmother, Herta Paczoska, who was a childhood neighbor of Pope John Paul II. Thanks to German classes he had audited just for fun at K, Meier was able to communicate with Herta, who spoke German in addition to the Polish her grandchildren spoke exclusively.

“They tried to teach me to count to 10 and to say the days of the week and the months of the year in Polish, and they would laugh their heads off at my inability to get it right,” Meier said. “Having audited German at K allowed me to interact with their grandmother, and long story short, she arranged for me to sing for the pope at a Mass in his private chapel.”

Meier only learned of the arrangements the night before he was to sing in the morning.

“I had not brought any sort of clerical garb with me,” Meier said. “So, then there’s this mad dash to find clerical garb, and longer story short, one of the guys had a polyester leisure suit and a clerical shirt that had been wadded up in a ball in a bag on the floor of his closet. So now it’s 1:30 in the morning, I have to be there at 5, and I am trying desperately to not melt the damn suit as I run an iron over it to try to get the wrinkles out.”

Meier sang Come, My Way, My Truth, My Life by Vaughan Williams and American hymn-turned-folksong How Can I Keep From Singing?

Afterward, L’Osservatore Romano, the official public affairs office for the Vatican, took photos of Pope John Paul II meeting Meier as well as each pilgrim in attendance. Meier later visited L’Osservatore Romano headquarters and bought prints of himself shaking hands with the pope.

“I got several prints,” Meier said. “I brought them back to the States, and I took one and had a negative made. With that, I made a photo Christmas card that said, ’Merry Christmas from the two of us.’ And that’s what I sent out that year.”