Writer: Zinta Aistars

Photography: Ron Leifeld, Samantha Pergadia, Katherine Simone Reynolds, Siyabonga Sikhakhane

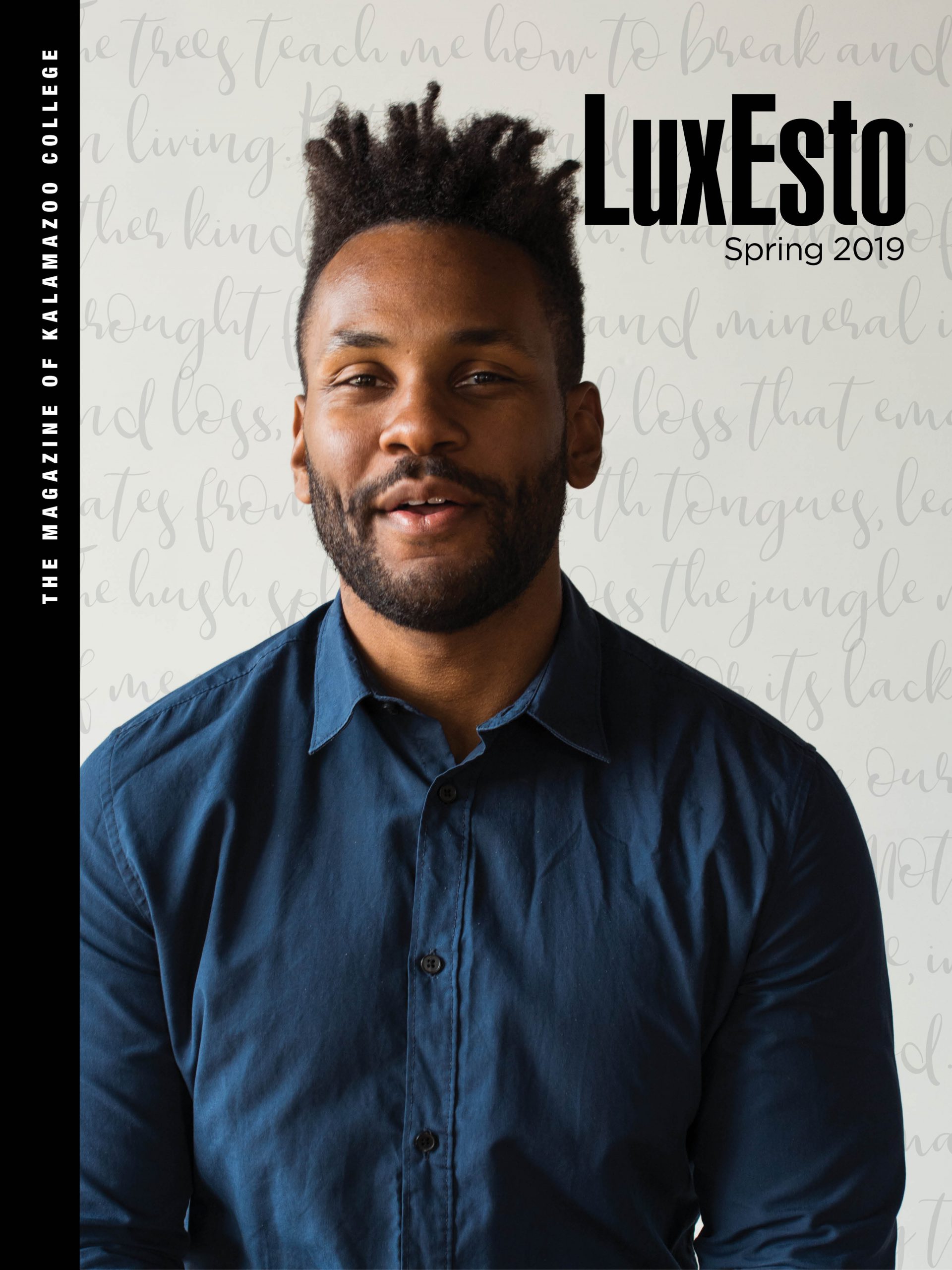

Abandon all stereotypes, ye who enter poetry. Football players, like Aaron Coleman ’09, write it. He even translates it. Why? Because you don’t want to “deny yourself anything that makes you feel alive,” he says. And he doesn’t. Poetry, for him, means capturing those moments of surprise encountered every day in life, moments that enrich life and give it meaning.

The West Bloomfield (Michigan) native has had his first collection of poetry, Threat Come Close, published by Four Way Books (March 2018), and attention is coming fast.

Coleman has won the Tupelo Quarterly TQ5 Poetry Contest and the Cincinnati Review Robert and Adele Schiff Award. He has been a two-time semifinalist for the 92Y Discovery Award, and his chapbook, St. Trigger (Button Poetry, 2016), won the 2015 Button Poetry Prize. Coleman is currently a chancellor’s graduate fellow in the comparative literature Ph.D. program at Washington University in St. Louis, but his journey to poetry began at Kalamazoo College, which began with football.

“Jamie Zorbo, at that time an assistant football coach at K [and now the head coach], came to my high school,” Coleman says. “I played football, basketball and track in high school. When I learned more about K, it got me excited—Eileen Wilson-Oyelaran was president, and there were changes happening. I wanted to be a part of that change, part of that growing inclusiveness and diversity. I take pride now in that.”

Mononucleosis sidelined him his freshman season.

“I couldn’t play again until my sophomore year, but by then I found my interests were changing,” Coleman says. “I decided to study abroad and went to Spain as a junior—it was everything I needed and more.”

During study abroad, Coleman began to see himself differently, and he began to consider writing more seriously.

“I saw myself in a different way. Not necessarily better or worse, but from a different angle,” Coleman says. “I was the only black kid in the student group. I had felt constricted back home by American racism. In the U.S., racism can tend to mean being seen as something less than fully human, less smart, less valuable. But in Europe it was more like xenophobia. In Spain I saw the white students experience what it was like to not be the majority voice anymore.”

Coleman’s coming to see himself differently included an epiphany on the power of words. He was immersed in the Spanish language, soon becoming fluent, and he also began to look at his native language in a new way. Coleman was a psychology major with an anthropology/sociology minor, but the call of poetry intensified. He began to share poems with Diane Seuss, the College’s Writer-in-Residence (now retired).

“She’s still an incredible mentor,” he says. His growing interest in poetry was part of a very busy final two years at K.

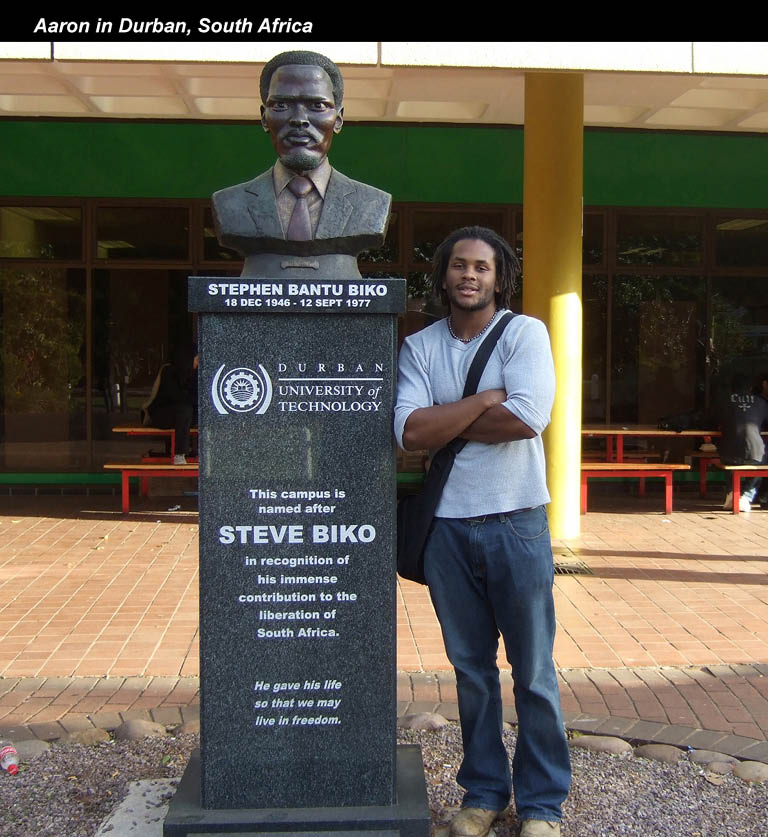

Coleman engaged in service learning at HYPE (Helping Youth through Personal Empowerment), a Kalamazoo Juvenile Home mentorship program, where he organized and led workshops; he led a poetry workshop at Kalamazoo Central High School, called Heartbeats; he was a teaching assistant in a program called Building Blocks, a community organizing project; and he traveled abroad for a second time on a K research grant, the Isabel Beeler Fellowship, that took him to Durban, South Africa, where he was a facilitator for a bilingual poetry project at the Mazisi Kunene Foundation.

After graduation, Coleman returned to Spain, this time as a Fulbright scholar, and he worked in Madrid for the next two years as a teaching assistant in English and poetry, starting a bilingual poetry festival for his students at IES Manuel de Falla.

“That incredible experience provided one of my first translation opportunities,” Coleman says. “An MTV crew came around for the 2010 European Music Awards, and they were looking for English speakers to translate in real time for the behind-the-scenes staff producing the show.”

Coleman gained a new, deeper respect and understanding for the challenges of translation.

“If I try to create a translation of a poem that is a clear-cut reproduction of the original, I will fail. It’s really a process of transformation,” he says. “Nearly equal amounts of creativity go into writing and into translation.”

Now a Ph.D. candidate at Washington University, where he earned a master of fine arts degree in poetry in 2015, Coleman has devoted his Ph.D. dissertation to translating the work of Afro-Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén, a contemporary of Langston Hughes.

“I’ll also be teaching a class at Washington University in the spring of 2019,” Coleman says. “It’s called ‘Black Constellations: Mapping Trajectories in 20th Century Black Poetics from Harlem to Millennium.’”

Coleman works hard to find a balance between teaching, translating and writing. Threat Come Close was a result of his conscious effort to keep his own writing at the forefront of his life.

“It deals with what Americanism and blackness are and can be, what masculinity is and can be,” he says. “It’s about what is possible when we invite a threat, or a risk, to come closer, rather than run away from it. Black men are often seen as a threat. I’ve tried to create a deeper connection and awareness of our history—the poems are a collection of reimaginings as I grapple with history. Poems don’t provide answers, but they do help us ask better questions.”

Writing poetry is not so very different from athletics, after all, Coleman says. On a football field or the blank page, Coleman says, “I’m pushing myself to an extreme in order to better know myself.”

Threat Come Close by Aaron Coleman

“Risk a bridge,” Aaron Coleman writes in his new poetry collection, Threat Come Close. Building bridges isn’t an easy task, but it is a necessary one. It requires “sheet rock cut open with explosives to force through/byways and sow man-high seas of crops, to make space for/interstates, for cold emergencies and tanks, and touch” (from “Very Many Hands”).

Coleman has been risking and building bridges most of his life, in seeking the meaning in his own life, in being black (in America and elsewhere), in masculinity, in history, in language. Although he was an athlete growing up (football, basketball, track) poetry entered his psyche early and grew in importance steadily, especially in college.

For Coleman, poems grew from the confluence of three major influences: First, an album by the hip-hop group, Outkast. Hip-hop introduced Coleman to the rhythms and musicality of language. Second, by reading and then writing a book review in high school about Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, Coleman began to think about race, history, coming of age and violence. Third, he watched a TV poetry series called the Def Poetry Jam, which exposed him to spoken word slams and the communities behind these slams.

All three of these early influences appear in Coleman’s poetry collection, written in his 20s, by which time poetry was a serious pursuit for him.

He explores his identity as a black man from multiple angles, from the fear he feels while moving through the world to the fear he inspires, as a black man, in others. The poems express the beauty of being black, the strength it gives him, its history that has become a part of him, and the threats and desperation it invites.

His work weaves a lifetime of youthful impressions that come together to form the adult man: the pain, the joy, the loneliness, the connection, the contradiction, the way forward. “…I am what was taken from me/and I am what was given back,” he writes in his poem, “These Miles.”

As with all great journeys, Coleman’s collection, Threat Come Close, unveils old and new scenery with each passing. It is the kind of journey a reader will want to traverse more than once, maybe even many times, making a new connection and deepening understanding with each passage. These are poems rich enough to give something new every journey.

Vice President for Advancement Al DeSimone • Associate Vice President for Marketing and Communication Kate Worster • Editor Sarah Frink and Jim Vansweden ’73 • Creative Director Lisa Darling • Project Manager Lynnette Pryor • Design and Animation Craig Simpson