By Sarah Frink

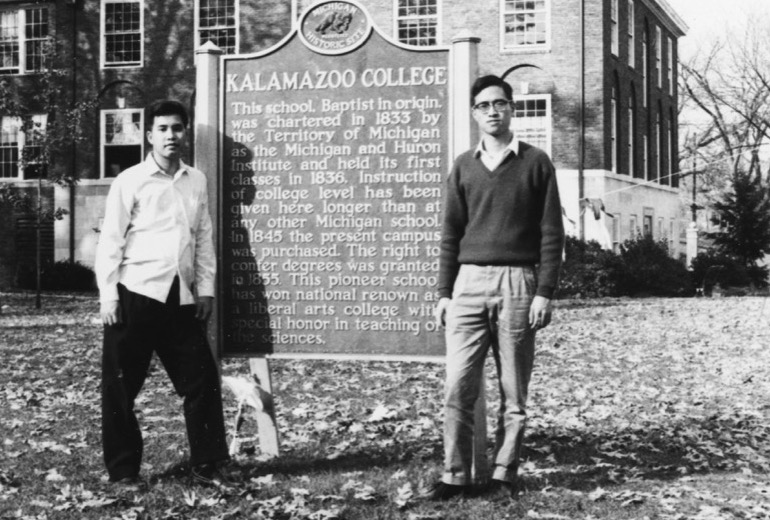

In the fall of 1963, two students travelled from Hong Kong to Kalamazoo, Michigan, to pursue their dreams. Each made the journey alone, unsure of what exactly they would find in this small Midwestern town with a funny name—yet they knew it would bring them one step closer to a better life. At K they found each other and became best friends. Almost 60 years later, their bond is as strong as ever, and their unconventional yet quintessential journeys to K and beyond have led to life-changing opportunities not only for themselves and their families, but for future generations of students as well.

The Small School with a Zoo in its Name

Alfred Lee ’66 was the oldest of six children—five boys and one girl—growing up in a poor neighborhood of Hong Kong. As a child, Lee’s family moved several times, living in small apartments with communal kitchens and bathrooms, apartments so small that there wasn’t room for a bed. The family didn’t have much, but Lee’s parents were always able to provide rice to eat and a roof over their heads. “We were thankful for what we had, and we were probably fairly lucky to have what we did.”

Lee was not the best student growing up—a bit of a class clown, always third or fourth from the bottom of his class. In middle school, he enrolled in the school where his father, a school teacher, was now the principal. At that time, Lee’s family was living in a tenement building that was four stories high, one of 10 buildings connected together. His father’s school was on the fourth floor, as was his family’s apartment. “The room we lived in was about 8’X10’; there was a bed for my mom and dad and the two youngest kids. The rest of us would roll out a bamboo mattress on the floor at night. The apartment had these milky white cockroaches…they were terrible!”

As the children grew and it became more crowded, Lee’s dad suggested he sleep in one of the schoolrooms, where he could pull together benches for a bed. One evening, as he was getting ready to settle in for the night, he spotted a book lying on the floor of the classroom. “I still remember the name,” Lee says. “It was Fundamentals of English.” He picked it up and flipped through it, studying it a bit before turning in for the night. It was the moment that would change his life.

Soon after, Lee took an English test in class and aced it. He chuckles as he recalls the teacher summoning Lee to his desk and saying, “You did pretty well…how did you cheat?” Lee says, “Most people knowing my background would have asked me this question. I said to him, ‘Honest to goodness, I didn’t cheat!’” The teacher sent Lee to see his father. “My dad just said, ‘C’mon, we know you too well. Just tell us how you cheated.’” Lee again protested his innocence, and his father decided to have Lee retake the test. “They set me down with a new set of questions and they watched me like a hawk—same result! They looked at each other and said, ‘You gotta give it to this kid, even with two pairs of eyes staring at him, he still managed to cheat!’” Lee laughs. “I said ‘I’ll show you!’”

Lee went on to secondary school, where he was number one in his class. He took the citywide Form Five exam at the end of school and did very well. The top 30 were granted a scholarship for what was called the matriculation courses—two additional, selective years of secondary school that would lead into university. Being from a large family, however, Lee knew he didn’t have the resources to go to college. Reluctantly, he turned down his scholarship and set out to find work.

Lee took a job at the Hong Kong International Airport in the control tower, a good paying job for a high school graduate. One day he saw an advertisement from the International Institute of Education (IIE), an organization that distributed scholarships to study abroad in the United States. Lee applied, and about six weeks later he got a call. Lee says, “The man at the office said, ‘Congratulations! We have a scholarship for you at Columbia University.’” The man told him that he would have to teach Mandarin while he was there. “I said, ‘I don’t think I know Mandarin well enough to teach it.’ And he looked at me and said, ‘No Mandarin, no Columbia.’” So Lee went back to his job at the airport. A couple of weeks later, the IIE called again. They told him, “We can’t send you to Columbia, but we can send you to Kalamazoo College.” Lee admits he nearly turned down the offer to go to the small school with a “zoo” in its name. “The man said something to me that I remember to this day,” Lee says. “‘Don’t be so impetuous, young man! What have you got to lose?’ And there I was, 21 years old, and I thought, he’s got a point.” So Lee went to the American information center to do some research. “I found out K was one of the top liberal arts colleges in the U.S.,” he says. “I thought, well, that’s pretty good!”

Lee gathered enough funds to buy his boat ticket and start his journey. When he got to the U.S., he took a train through Chicago to Kalamazoo. “I had a very good first experience in Kalamazoo. I’m standing in the station with my two suitcases and my thick winter coat, at a loss for what to do next, and this nice woman came up and said, ‘You look kind of lost. Where are you going?’ And I said, ‘Well, I’m from Hong Kong and I’m going to Kalamazoo College.’ She said, ‘Well, I’ll give you a lift,’ and she took me all the way to Hoben.”

A Bond is Formed

Chung Wu ’66, meanwhile, had a slightly different path to Kalamazoo College. Wu grew up in a middle-class family in Hong Kong. Wu went through the technical high school system, which in addition to language, mathematics and science classes, included classes such as woodworking, metalworking and engineering. Unlike Lee, Wu was able to pursue his secondary education after Form Five. For two years, Wu went to Kings College, where he studied physics, chemistry and mathematics. “We already started to specialize in Form Six; every student chose three to four subjects. I chose the science path.”

Like Lee, he applied for scholarships to study in the U.S. through IIE. “Kalamazoo College was generous enough to give me a full scholarship. And of course at that time, I hadn’t heard of Kalamazoo, like many people outside of Michigan or the Midwest.” His first impression of K was “wonderful.” He says, “In Hong Kong we were used to the idea of specializing early, so the idea of a liberal arts education was a little bit strange to me. Now I really appreciate that aspect and wish I could have taken more of those subjects outside of science and mathematics.”

Lee and Wu did not know each other in Hong Kong, though they later discovered that Wu’s older brother took his high school exams at the same time and place as Lee. “In those days, there were not too many foreign students, especially not from Hong Kong. We were very homesick, so after we met at K, we stuck to one another,” says Wu.

Both students were hungry to learn. Lee says, “Since Chung had his two additional secondary years, one of which was a year of university equivalency, he didn’t want to start at K as a freshman. He wanted to be a sophomore. He figured that there was strength in numbers and my command of English was a little better than his, so he said, ‘Let’s go talk to the dean.’ And we went in to talk to Dean [Paul] Collins, and I was preparing for a battle. I had rehearsed all my reasons why we should be sophomores. To our great surprise, without hesitation, he agreed.” It turned out that technically, they were at K as exchange students, and were therefore only supposed to be at the College for one year. Freshman, sophomore…it didn’t really matter, so the dean readily went along with their request.

Lee and Wu enrolled in sophomore classes. Wu says, “I was a nerd. I was crazy about studying, trying to learn as much as I could about physics and math.” For Lee, it was more of a challenge. He had been out of school working for a couple of years by this point. So Wu tutored him through calculus and electricity and magnetism, until Lee got caught up. As for their one-year exchange…both Lee and Wu did so well academically, the Dean was able to procure scholarships for them, to allow them to stay and earn their bachelor’s degrees.

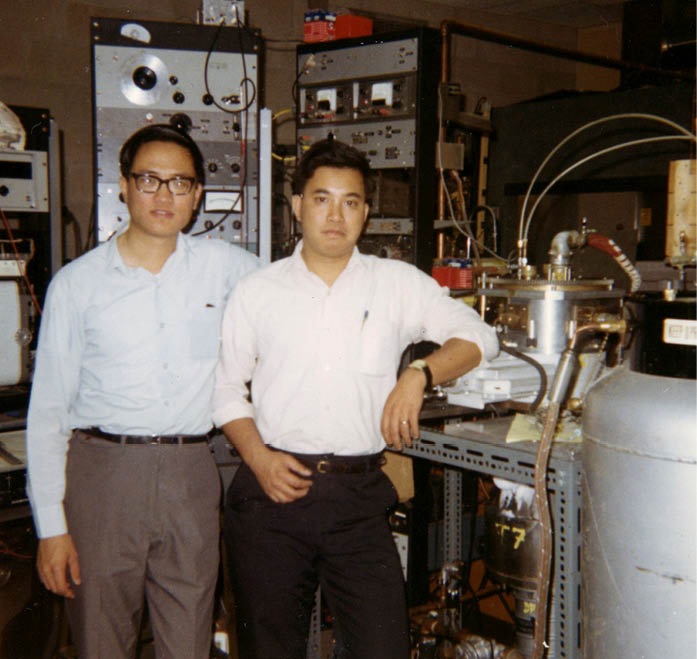

Lee and Wu joined the same fraternity at K, the Delmega Society, and took part in the same accelerator project in the physics department. They went to fencing classes together and played ping pong in tournaments. Dr. Wright in physics was Wu’s most formative mentor, and they still stay in touch. He was also very fond of Tish Loveless, who taught them fencing. For Lee, Dr. Ralph Deal was a strong influence. “I remember the first time I met Dr. Deal,” Lee says. “I went to the Mandelle library and saw him squatting between two racks of books, flipping through books. Coming from Hong Kong, where the professors can be extremely snobbish—they would die before being seen by a student sitting down on the floor. It made such a strong impression on me.”

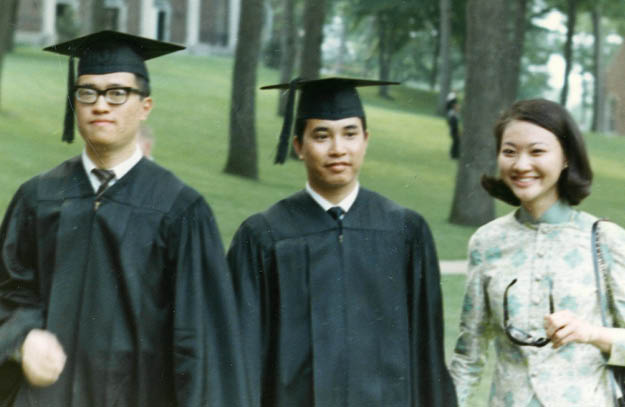

As graduation approached, they applied to graduate school. Wu was accepted to Yale, and tried to convince Lee to go there also. Lee earned an assistantship at Harvard, and was accepted at Yale with a scholarship, so he was torn. The assistantship required 12 content hours of teaching, plus prep. “My girlfriend, Nancy, was in Boston—we weren’t married yet—so between teaching and classes and visiting her, I thought, when would I sleep? So I chose Yale.”

From Theoretical Chemistry to Finance

Lee’s area of study was molecular dynamics. He studied with Dr. Richard Wolfgang, a pioneer and leading expert in the field of “hot chemistry.” When Lee first got to Yale, Wolfgang was embarking on a two-year leave of absence to Colorado, where he was forming a team to study molecular beam dynamics. Lee followed, giving him the opportunity to work with some amazing minds, including Dr. Dudley Herschback, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1987.

In 1970, Lee earned his Ph.D. in theoretical chemistry and went on to do post-doctoral work in Colorado and the University of Washington. At that time, the Nixon administration was making cuts in federal funding for scientific research and development, and Lee was unable to secure a faculty position. While he could have pursued further post-doc work, by this time Lee and his wife Nancy were married with two children. “She told me it was time to get a real job,” Lee laughs.

Lee shifted gears entirely and started a new career with Lincoln National Life, first in sales and eventually as director of agency development. He took over an agency for a few years, then went out and established his own company, specializing in personal financial planning, particularly estate planning. Today Lee and Nancy are happily retired. Their oldest daughter, Karen, is a University of Chicago law school graduate married to a fellow law school graduate, and a partner in her law firm. Their son Paul is an emergency room physician. Their second daughter Vicki married another University of Chicago law school graduate. Their youngest daughter Grace is also a Chicago law school graduate married to a fellow graduate. “They’ve all done very well for themselves, and we are very, very blessed,” Lee says.

Engineering the Future of Aviation

Meanwhile, Wu went to Yale with the goal of becoming a research physicist. He earned a Master of Science, Master of Philosophy and a Ph.D., and then went to work at the University of Singapore. “I was given a contract of three years, teaching electrical and electronic engineering,” Wu says. After his contract was up, he decided to move to Canada, which offered more advanced research opportunities than Singapore. A professor he knew from Yale was in Montreal, so Wu accepted a research associate position with him. He worked for him almost two years, researching magnetism and polymer physics, before finding a position in Pratt and Whitney Canada designing and building jet engines. “Pratt and Whitney Canada was a subsidiary of Pratt and Whitney in Connecticut, where they built the big engines. In Canada we had smaller projects—similar technology, smaller in size.” Wu worked there for more than 20 years before transferring to Connecticut. “There was technology that I invented and developed in Canada that the head office had interest in applying to their big engines. I worked there for 15 years on the same technology, which has to do with the design and manufacturing of fans and compressors in jet engines. I spent 32 years on this technology. When I felt like it was fully developed, I decided it was time to retire.”

Wu and his wife, Hing, now live in Bellingham, Washington, close to family and friends. Wu and Hing met in Hong Kong his last year of high school. After his first year in graduate school, Hing joined him in the U.S. and studied library science at Simmons College in Boston. They married in 1969. “She was very career-minded, so even though we moved to Singapore and started having our children, she kept working. And every time we moved it was because of my career requirement. She changed her workplace quite a few times because of such moves, so I’m really thankful to her for that.”

Their son Kai was born in Singapore. Kai studied physics at Cornell, earned a Ph.D. in renewable energy, and worked in computer-related fields for a number of years; he’s now working at a start-up company in the area of plant-based whole foods. Their younger son, Tsan, was born in Montreal and was very interested in humanities and social sciences. He learned several languages in school and in his travels around the world. “French, English, Chinese, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, German—he could pick them up, just like that,” says Wu. Sadly, Tsan passed away at the age of 23. The Wus established a scholarship at K, the Tsan Wu memorial scholarship, for students who study foreign languages and culture, to commemorate Tsan’s love for travel and the humanities.

Lee, too, is working with K to establish a scholarship. This one will be for international students, inspired by his own experiences. “I would never be where I am today without the opportunities that K has given me,” Lee says, “and I would like to make it possible for someone whose background might be similar to mine to be able to have the opportunity to move ahead.”

The Journey Comes Full Circle

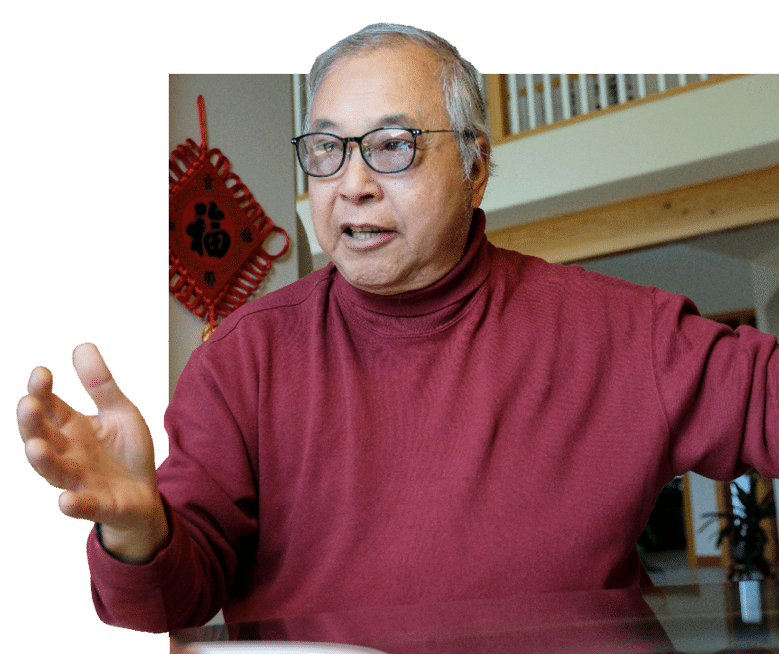

Now that they are both retired, Lee and Wu are able to visit with one another several times a year.

“At K, we often talked about our future plans and wondered what our future would be,” says Wu. “Whenever we meet now, we talk about K—the professors and our friends.” Wu says. He smiles. “As the years have gone on, our friendship has become more meaningful. We’ve influenced one another in ways we didn’t even realize.”

Like Lee, Wu deeply appreciates the opportunities that his K education provided, and is grateful to be able to support similar experiences for future students through a scholarship.

“Kalamazoo College was so kind to us. It changed our lives, broadened the opportunities. When I was in high school in Hong Kong, I was thinking I would go into a teacher training college and teach school. I saw this as the only opportunity. If that didn’t work out, I would be an office helper. That’s what a lot of high school kids did in those days. Getting a scholarship from K, that made all the rest possible. It is something we can never pay back enough.”

Lee went from working in the control tower at the Hong Kong International Airport to earning a Ph.D in theoretical chemistry, thanks to his opportunity to attend K on a scholarship.

After K, Wu went on to earn a Ph.D. at Yale, and spent much of his career designing and building jet engines for Pratt and Whitney.

Wu and Lee enjoyed spending time in the physics lab. “I was crazy about studying, trying to learn as much as I could about physics and math,” Wu says.

Wu and Lee share a deep affection for Kalamazoo College and hope to provide similar opportunities for aspiring students through endowed scholarships.