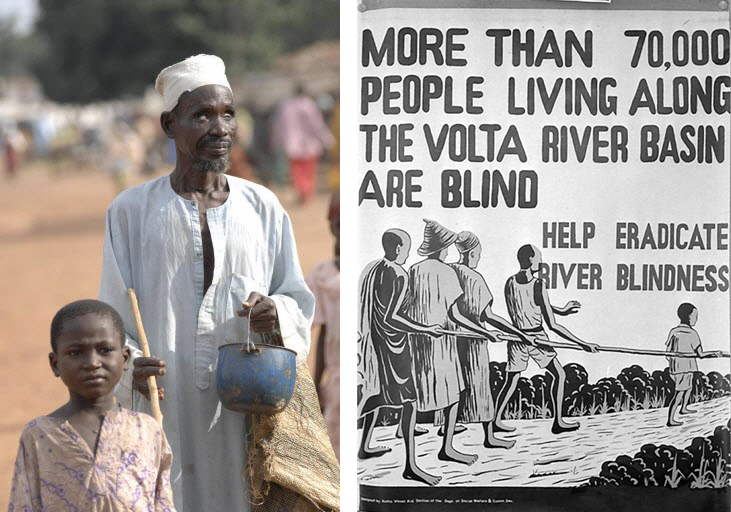

The agony was almost unimaginable. For generations, the people of sub-Saharan Africa were afflicted by a disease called riverblindness, or onchocerciasis, caused by a parasite transmitted by a blackfly. Villagers living near rivers, where the blackfly breeds, have long endured the horrible itching caused by the disease that would eventually lead to the loss of vision.

Bruce Benton ’64 explains: “What happens is the fly lays its eggs along the banks of rivers, and so the disease is usually worst near the river. The fly transmits a parasite that develops into a worm about two-and-a-half feet long that lives in the body for 14 years. It produces millions and millions of microscopic worms. The worms cause this horrible, intense itching, and at the end stage of the disease, they go into the eyes. You get tunnel vision—and eventually—permanent blindness.”

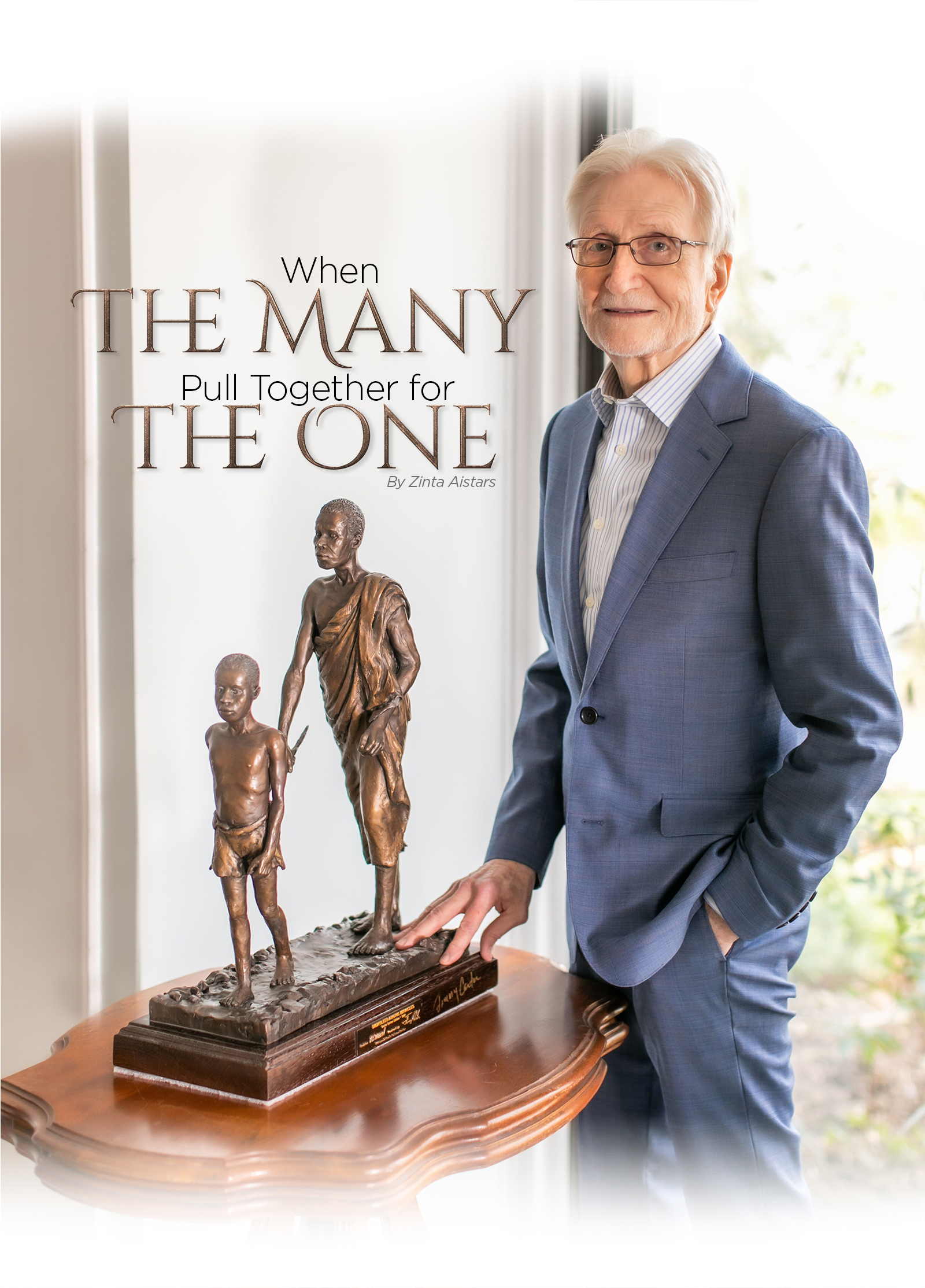

For 20 years, Benton led two international programs at the World Bank—the Onchocerciasis Control Program (OCP) and the African Program for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC), covering 31 African countries between them—to bring the disease under control. He documents the disease and the efforts to control its spread, if not yet eliminate it, in his new book, Riverblindness: Taming the Lion’s Stare (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020).

“The book presents a complete story of the discovery of the disease and the effort to control it in Africa, going back as early as the late 1800s,” Benton says. “The effort to control it started in 1974 with an ambitious program that covered 11 countries in West Africa, where the disease was thought to be the worst in the world. It was launched by Robert McNamara, who was president of the World Bank at the time.”

Benton says that it was during his study abroad experience at Kalamazoo College that he became interested in other cultures. Spurred to make a difference in the world beyond his personal borders, he earned his degree at K in history and economics. He earned graduate degrees at Johns Hopkins University and University of Michigan, then began a 40-year career focused on development assistance for Africa.

Benton was responsible for commodity negotiations and the international development banks in the Office of the Secretary of the U.S. Treasury throughout the 1970s and advised Congress on foreign assistance before joining the World Bank in 1982. In his role at the World Bank, Benton mobilized financing for the program to end riverblindness, raising more than $750 million.

“The idea was to not only control the disease, but then look at ways of promoting development in those areas where the disease was the worst and begin to increase agricultural production once the disease was brought under control,” Benton says.

Because the black fly larvae hatch along riverbanks, where land is the richest for farming, people living there would move away to avoid the disease, but in so doing, lost their ability to live productively off the land. Poverty became a side effect of the disease, and conversely, eliminating the disease has raised the living standard of these communities. One analysis conducted by Benton and World Bank economist Aehyung Kim estimated that 1,199,000 cases of riverblindness were prevented by the Onchocerciasis Control Program over the span of 1974–2012, and as a result, the program added 13,091,991 years of productive labor to the rural economies of the 11 OCP countries.

The World Bank created unique partnerships involving UN agencies, donors, NGOs, the pharmaceutical company, Merck, universities, African governments and the stricken communities themselves to effectively control the disease. Benton says a means to control it is now available as an oral medication called ivermectin, which reduces transmission by killing the microscopic worms in the body that cause intense itching and eventually blindness. It must be administered on an annual basis for at least 14 years —the lifespan of the adult worm, which ivermectin does not kill. The drug is also commonly used to treat other parasites in humans and animals, including heartworms in dogs. The Merck scientist who discovered ivermectin, Dr. William Campbell, won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2015.

“There were more than 100 partners involved, and they all pulled in the same direction,” Benton says. “We had a clear objective that everyone agreed upon and a strategy for achieving that objective that was clear and consistent over time.”

So many of these organizational skills—along with the desire to solve big problems and help people—Benton attributes to his formative years at Kalamazoo College.

“I grew up in the Midwest—in Columbus, Ohio,” Benton says. “I really hadn’t been out of the Midwest much until I went to Aix-en-Provence in France for foreign study my junior year, which was 1962-63. It was a real eye-opener for me to live in another culture, live with a family, become fluent in French. I loved it.”

The world had suddenly grown bigger for the young Benton. Upon his return to Kalamazoo, Benton decided his next reach outward into the world would be through Peace Corps. Being fluent in French enabled him to travel to Africa, to regions where French was a predominant language. He traveled to Guinea, West Africa, where he taught English as a foreign language along with math and physical education.

“That was again eye-opening,” he says. “I saw the need in sub-Saharan Africa, the poverty. These are wonderful people, but they needed to be supported. I concluded from that that I wanted to go on into economic development with a focus on Africa.”

When Benton began his career at the U.S. Department of Treasury and then the World Bank, he realized his goals to create a difference in Africa.

“The Kalamazoo College education was ideal for this,” Benton says. “It was very rare for small liberal arts colleges to have foreign study programs in the mid-1960s, so I was very fortunate to wind up at Kalamazoo College and have that experience.”

Benton recalls that it was an issue of Newsweek magazine that was on the stands at the time that inspired him to take a closer look at Kalamazoo College. The issue listed Kalamazoo College among the top 10 small liberal arts colleges in the country.

“I visited all of them,” Benton says. “I selected Kalamazoo because it was small, it was pretty, and I thought I could play football.” He laughs. “When I got there and started studies and tried out for the team, I realized I couldn’t do both. Just as well. Our class was the first to go overseas.”

Benton says he valued “the small classes, the ability to know your professors on a fairly intimate basis and be able to talk to them—that was really important—and a small student body so that you could get together, brainstorm, do things together. It made learning fun.”

On a trajectory from the small to the big, Benton now looks back on successful programs to gain control over onchocerciasis. Comparisons to the current worldwide pandemic of COVID-19 are not lost on him.

“Both diseases are similar in that it’s impossible to keep them out of a country—COVID-19 due to international travel and riverblindness due to the long distance traveled by the blackfly vector. Consequently, go it alone, nationalist approaches are doomed to fail. Our interdependency precludes it. Multi-country collaboration is essential to bring both diseases under control. Fortunately, for riverblindness, this was understood from the very beginning and a regional approach focusing on intercountry, intersectoral partnership was adopted. That’s in large part why it worked. By contrast, we failed to do this with COVID-19 and have paid a heavy price, particularly in the United States.”

Nevertheless, Benton is confident that the lessons learned from the riverblindness programs can have long-lasting impact on world-wide approaches to disease control.

“There are a few things in the works,” he says. “Because this is the story behind the first effort to control a major neglected tropical disease, and it was very successful, there has been a lot of interest in the book. There’s a symposium in February 2021, sponsored by the Task Force for Global Health, an organization based in Atlanta that focuses on the world’s most intractable diseases. They are basing the symposium on the book and my findings on what worked in controlling this disease and the extent to which these lessons might be applied to other diseases. They will discuss the various themes of the book—partnership, the regional approach, achieving human and rural development through disease control, and the use of drug donations to address an endemic disease.”

Benton says other similar symposiums are also planned, including one upcoming at Johns Hopkins University and another at Georgetown University.

“Lessons learned from our work with riverblindness can be applied to a broad range of global health programs to control and even eliminate diseases,” Benton says. “With similar approaches of collaboration between partners in government, in business, in health care, all working together toward one consistent and clear goal, we can show compassion to many of the poorest populations across the world.”![]()