By Andy Brown

A love of documentary films that began in K’s English program has turned an alumna into an award-winning producer and an ally in raising underrepresented voices in show business.

Christine Cho ’17—a Korean-American producer, writer and graphic artist living in Los Angeles—served as the producer of Lakutshon’ Ilanga, or When the Sun Sets, as a part of her graduate thesis at Chapman University in Southern California, where students choose from specialties such as directing, cinematography, producing, editing, sound design and production design. The film is a short drama about Lerato (Zikhona Bali), a young Black nurse in South Africa in 1985, as she begins a journey to look for her missing brother. Her brother, Anele, played by Aphiwe Mkefe, is involved in the resistance against apartheid when he disappears.

Based on a true story, the film is written and directed by Phumi Morare, a native South African filmmaker and peer of Cho. When the Sun Sets earned several well-known awards including the 2021 HBO Short Film Award at the American Black Film Festival, the NAACP Image Award in the Short Film category, and Narrative: Domestic Schools category honors at the Student Academy Awards. The film was also shortlisted for the 2022 Academy Award in the Live Action Short Film category, and its additional award nominations included Best Student Film at the 2021 Austin Film Festival, Best Live Action Film at the 2021 British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Student Awards, Best Short Narrative at the 2021 Blackstar Film Festival, and special mention for Best South African Short Film at the 2021 Durban International Film Festival.

The film’s success has, at times, been overwhelming for Cho.

“It’s been a lot to wrap my head around for me and the whole team,” she said. “We’ve gotten way more than we bargained for. To sum it all up, I’m eternally grateful for all the opportunities that we’ve had and the opportunities that we were given. It feels like it’s gotten to be an extended education, for myself and for the rest of my team.”

Before production, it was Cho’s responsibility as a producer to hear pitches from film writers and directors in the Chapman graduate program before selecting which project she wanted to pursue.

“I was getting started on the film toward the end of my first year at Chapman in 2019,” she said. “When I started speaking with directing students about their scripts, they would pitch their film to me and I would just talk through their ideas for it. This film just stood out to me from the rest.”

When the Sun Sets stood out to Cho partly for the proposal itself, which incorporated actors of color, and partly because the writer and director wanted to shoot abroad. The film takes its title from a song of the same name written by Miriam Makeba, a South African singer, songwriter, actress and civil-rights activist who was sometimes known as Mama Africa until her death in 2008. Makeba is associated with Afro-Pop, jazz and world music as well as her own fight against apartheid.

“During the development of a film and in pre-production, a producer tends to be very hands-on, although everyone has their own style,” Cho said. “For some people, the role isn’t very clear-cut. Sometimes the role is as a financier. Other times, the producer can be one of the first people brought on board to the project or they could be the person who found the script to begin with and worked with the screenwriter. From that point, maybe they hired the rest of the crew, including a director and cinematographer.”

With her production, Cho was responsible for ensuring that the film’s behind-the-scenes logistics were running smoothly, which was a tough job considering the challenges of funding the film.

“It was a long process of raising funds to shoot the film, taking into account travel costs and everything else that we would need to secure once we were out there,” Cho said. “All the drafts of the budget that we were putting together were quite high, so we spent almost a year raising funds, applying to grants, writing proposals and pitching the project to various people. It was a long thinking process.”

Plus, the COVID-19 pandemic nearly forced the entire production team to go home indefinitely.

“It was March 2020 when we finally flew to South Africa,” Cho said. “We had no idea what was in store for the world at that point. COVID-19 was a huge, unprecedented piece of our whole journey, and I honestly can’t even tell you how it worked out. We were keeping our heads down and praying as we just kept going while knowing that at any moment the university could call us home. We were shooting in mid-March while waking up every morning to all the headlines. We saw the news of everything happening with COVID in the United States and it looked like the world was ending. We just kept pretending, shooting and finishing the film that we needed.”

The film, despite those troubles, prompted reviewers in the South African media to call the film skillfully executed and deeply poignant, painting a vivid picture of the injustices under which South Africans lived. Show business publications and podcasts throughout the Los Angeles area have interviewed Cho about the successful production. When the Sun Sets is now available to stream on HBO Max.

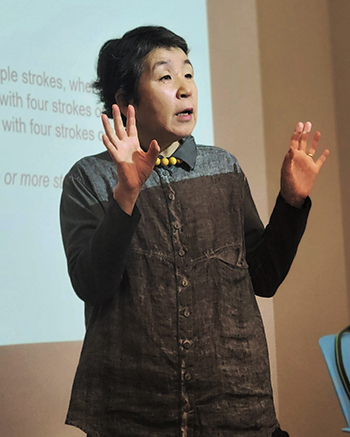

At K, Cho worked as a teaching/production assistant for the advanced documentary film class, participated in the Frelon Dance Company and studied abroad in Bonn, Germany. She also was among several students from Visiting Instructor of Art Danny Kim’s videography classes who interviewed Jeremy Sabella, the author of the companion book to a PBS documentary, An American Conscience: The Reinhold Niebuhr Story, which was screened at K during the 2017 Thompson Lecture.

“I took my introduction to documentary film class with Dhera Strauss before she retired after a long teaching career at K,” Cho said. “I learned so many fundamentals through Dhera and really found my initial spark for filmmaking through her class. When I went on to take the advanced documentary filmmaking class with Danny, I was intrigued at being able to learn from two very different filmmakers. Danny helped me to really stretch my visual storytelling boundaries. After completing Danny’s class, I went on to become a teaching assistant and I worked shifts in the edit lab to assist the current students of his class with editing their films. I also worked with the other TAs to organize the quarter-end film festival for the class, and we wrote and directed a silly teaser intro video for the festival with the students of the class per the yearly tradition.

“The Sabella interview was my very first on-set experience for a work that was going to be broadcast,” she added. “It was amazing of Danny to provide us the opportunity to attend and observe the production. We were working with our own equipment, so we could focus on engaging with Jeremy, finding the right compositions for the frame, and filling new roles that we hadn’t encountered before, like marking the clapper before each take. Thinking back on it now, it’s so nostalgic because I hadn’t realized at the time that it would become my first on-set experience out of many more to come.”

Those experiences and more gave Cho the encouragement and foresight to seek success in filmmaking through graduate school. She is grateful to Strauss and Kim for shaping the beginnings of her filmmaking journey and supporting her advancement to Chapman University with their recommendations.

“After graduating from K, I was thinking back to my experiences there, and how I had taken the documentary film classes that were offered,” she said. “I was able to reflect on what I really wanted to do. That propelled me to apply to Chapman and move out here to California, so K really helped give me the push I needed, and the culture itself, just shaped me as an individual.”

As for Cho, she hopes to continue working in filmmaking while continuing to elevate themes similar to those explored in When the Sun Sets, such as racism and marginalized identities. She considers herself to be a proponent for social activism and diverse representation and is interested in presenting multi-dimensional and layered people of color as characters who subvert expectations and reshape the way audiences relate to the human condition.

“It’s pretty important for this industry to keep pushing forward with underrepresented identities,” Cho said. “We’re through the apartheid era, but there’s been this idea that racism is over. I think a lot of people can say that that’s not the case. It’s still very present in that it lingers in the generations. There are a lot more stories to tell from that era, and more broadly, in the stories of people of color to begin with.”