by Zinta Aistars

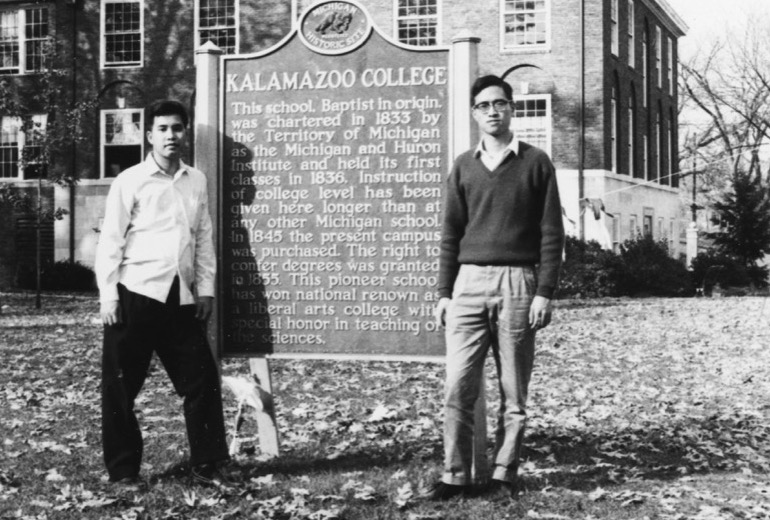

When Harold Phillips ’88 filled out his SAT and ACT tests in preparation for college, he made sure to check the boxes requesting information on various institutions. Colorful brochures soon arrived, touting the qualities of each college and university. Phillips set the stack of brochures aside to read aloud to his grandmother.

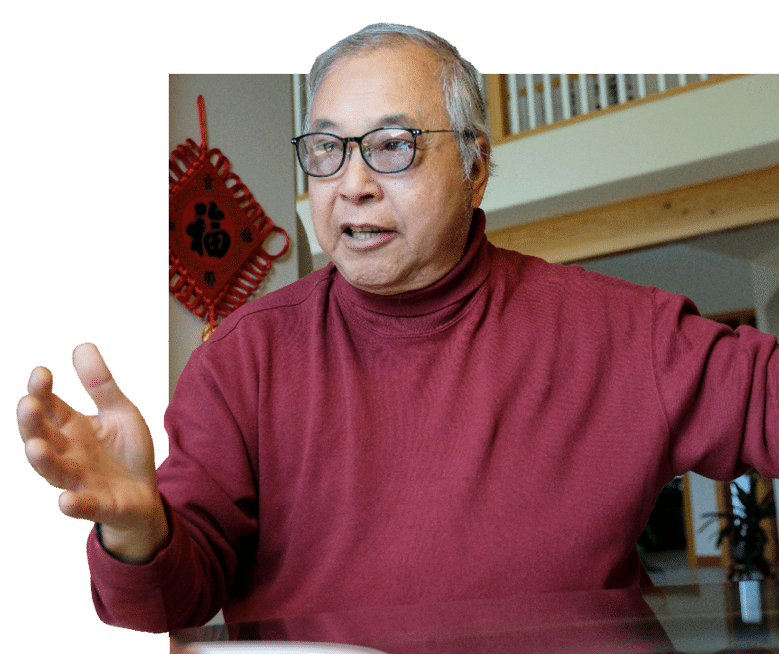

“I started reading the brochure about Kalamazoo College to Grandma, and she just lit up,” Phillips says. “She burst into song, singing Glenn Miller’s number, I’ve Got a Gal in Kalamazoo. So I set that brochure aside for a closer look.”

The K-Plan with its promise of study abroad…the small and intimate size of the student body…the rich curriculum…

Phillips liked what he saw when he took that closer look. He asked his mother if they could travel to Kalamazoo from their home on the south side of Chicago for a campus tour.

“I fell in love with K,” Phillips says. “Out of all those brochures, Kalamazoo College was the only place I applied—that’s something I would not recommend to others, only applying to one college—but it certainly worked for me. I knew I had to be there. ”

Phillips knew what he wanted. He had wanted to be a lawyer since he was 11 years old.

“I grew up in a neighborhood that wasn’t the best, and I saw a lack of representation that colored the lives of the members of my community,” he says. “I’ve always wanted to help people.”

Phillips took on a double major—political science and English. Yet as he immersed himself in his studies, campus life, and giving back to the college community, doubts began to arise. His studies at K were opening his mind to a wider range of possibilities.

“I told my advisor in political science that I wasn’t sure any more about being a lawyer,” Phillips says. “And he said it’s ok to not have all the answers, that it was important to be a lifelong learner. He told me to keep asking questions.”

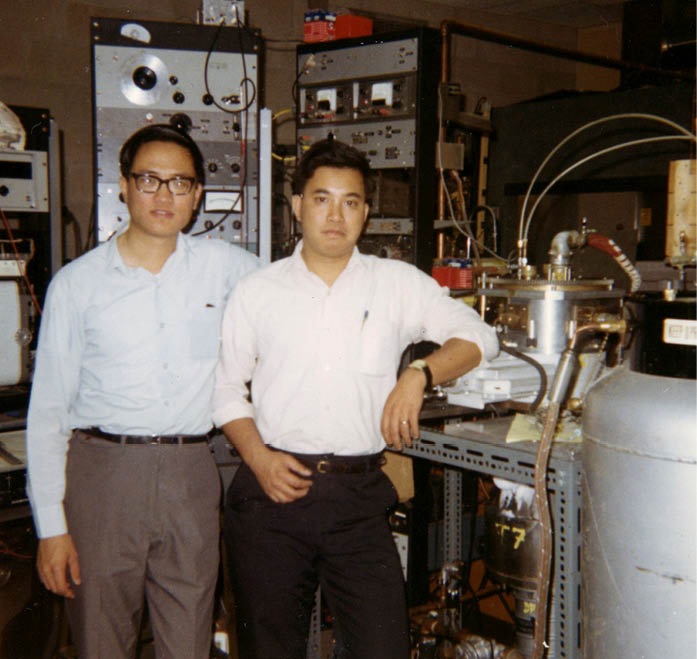

What held firm in Phillips’ mind was his desire to work at something that would help others, especially those who are in some way marginalized. He explored possibilities on the outer edges of a legal career. For example, during his sophomore year, Phillips worked with Dr. Wen Chao Chen at the Kalamazoo College Mary Jane Underwood Stryker Center for Civic Engagement. He worked on a project to make the Michigan Supreme Court more “user-friendly” by providing information in the most plain, everyday language possible. He says, “The court itself was an overwhelming institution for most people. It was important that we provided as much communication as possible before individuals arrived, and once individuals arrived, they needed information about the process, including the expectations and how to interact with the court system.”

During his junior year, Phillips lived for six months in Strasbourg, France, on study abroad. It was his first time overseas.

“I took full advantage of that experience,” he says. “There were about 20 of us K students living in dorms, but we visited a local family on weekends. I traveled across Europe, taking a train to London, Manchester, Scotland, Amsterdam, Venice, Florence, Rome, Paris, Brussels, Monte Carlo—dreams from my childhood were coming true.”

During his senior year, Phillips went to Washington, D.C., to work on his SIP—his Senior Individualized Project—which focused on how political expression can sometimes turn into terrorism when people are marginalized and feel they no longer have the means to express themselves.

“I suppose that was a project ahead of its time,” Phillips reflects. “I researched people who felt their humanity had been taken away from them.”

After graduation, Phillips headed back to Washington and spent a year at a large law firm. Then he worked in real estate law for a couple of years, where he learned the business of mortgages, deeds, title searches, real estate closing and refinances. This was the early years of gentrification in the capital, when affordable housing options in the city began to shrink.

“I kind of stumbled into urban planning,” he says. “I thought that might be the direction I wanted to go, developing housing for the elderly and disabled.”

He began working on a master’s degree in urban and regional planning at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It was the early 1990s, and Phillips wrote his thesis on the housing crisis among people diagnosed with the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV. While still in school, he helped to set up a housing project in North Carolina, the first of its kind in the state, for people affected by HIV.

After earning his master’s, Phillips returned to Washington, where he continued working on HIV prevention, learning federal grant requirements and helping small community-based organizations across the country, as well as South Africa, in 1996. He joined the federal government in 1997, working for the Health Resource and Services Administration in the HIV/AIDS Bureau in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

“Back in 1997, HIV was a death sentence,” Phillips says. “Today, it’s a chronic disease, a manageable disease. Our challenge continues to be getting the word out about the medications that are available today, about overcoming the racism and stigma associated with the disease.”

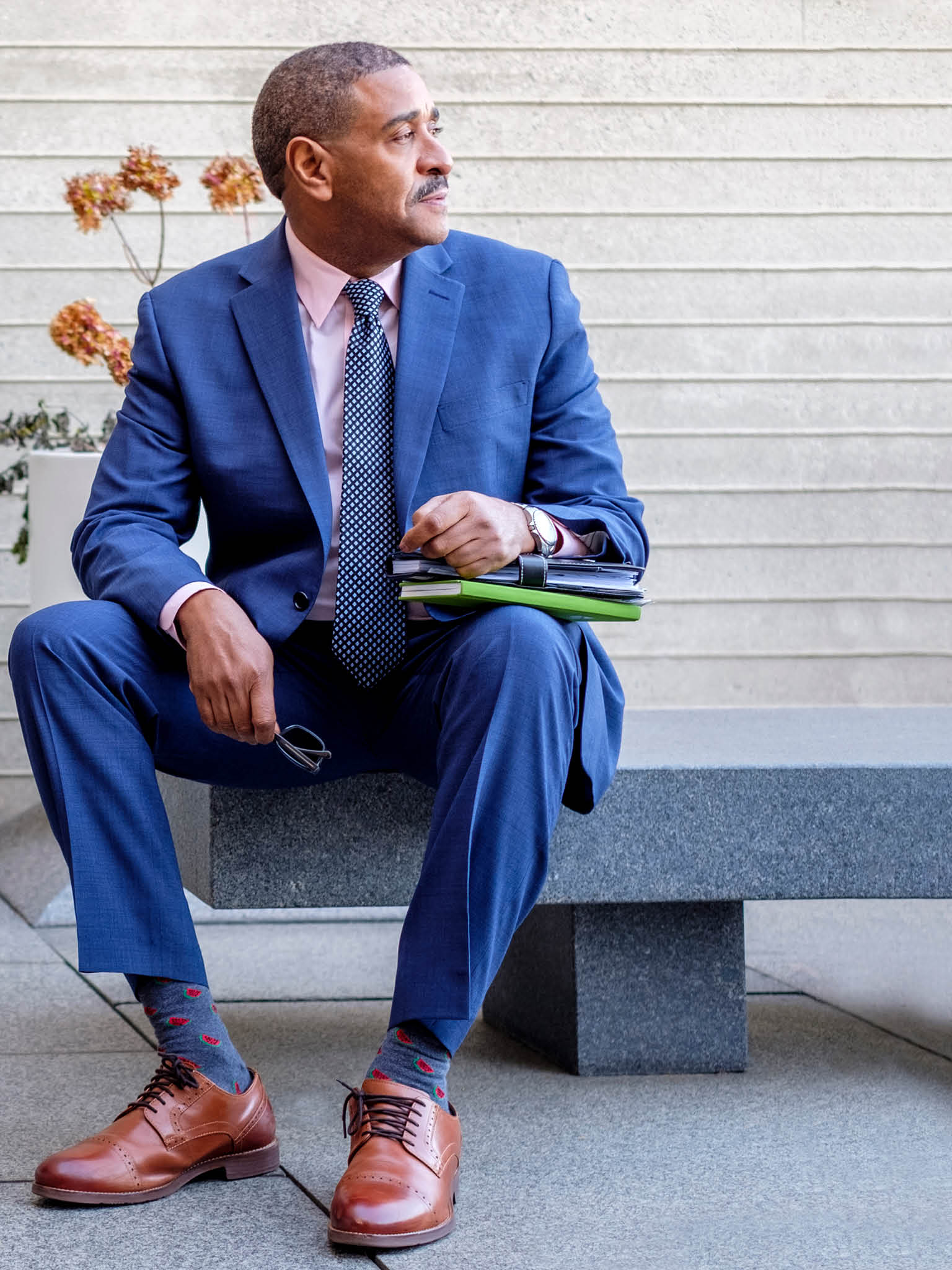

In September 2019, Phillips rose to the position of senior HIV advisor in the United States Department of Health. He will be coordinating and managing federal efforts to end the HIV epidemic within the coming decade and encouraging state and local governments and communities to join in this effort to end HIV.

While HIV may no longer be a death sentence, sexually transmitted infections and viral hepatitis are on the rise, Phillips says.

“We have to get people to understand this fight is not over,” he says. “Young people are heavily impacted, not just the gay and bisexual population. Women make up a third of those living with HIV, and 59 percent of those women are African-American. We need to get these populations tested and treated.”

Phillips says the U.S. Department of Health launched a new program in December 2019 that will work to prevent HIV before it happens. The initiative is called Ready, Set, PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis medications).

“We want to get two new and highly effective medications—free of cost—that can prevent HIV in vulnerable, high-risk populations prior to exposure,” Phillips says. “We estimate about one million people could benefit from this. The initiative has a goal of reducing infections by 75 percent over the coming five years and at least by 90 percent over the next 10 years. We will diagnose those who are not yet aware of their status and quickly link them to treatment so that they are virally suppressed and can’t transmit the disease to others. Treatment for those who have HIV, comprehensive prevention that includes medication to prevent getting HIV, syringe exchange programs, and condom distribution are all part of the effort to end HIV.”

Since 1981, more than 700,000 lives have been lost to HIV. More than 1.1 million people are living with HIV today in the United States with nearly 38,000 people newly diagnosed each year. In 2018, young people ages 13-24 accounted for 21 percent of new HIV diagnoses, Phillips says.

The Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative partners with federal agencies and leadership in state, city, county and tribal health departments to work with health care facilities, health care associations and the business community to reach high-risk populations. Community- and faith-based organizations along with academic and research institutions will also be brought into the circle.

“The initiative has four pillars for the goal of reducing transmissions—diagnose, treat, prevent and respond,” Phillips says. “We can end this epidemic. Science tells us this can be done. We must be innovative and work to reach disenfranchised communities who don’t trust government agencies or health care institutions. We need to listen to the community and have them tell us how to redesign support and medical services to improve our efforts to reach them. A large part of this effort is to remove the stigma of HIV and AIDS.”

Phillips voice warms as he recounts meeting a 24-year-old HIV patient who had gone to school with dreams of becoming a great dancer. The young man had learned that he had HIV when he was 20, and his disease progressed, as he had no knowledge of the care available to him.

“He didn’t know,” Phillips says. “Help was available; he didn’t know. He spent three years believing his life was over. He later found out about his options and may yet go back to fulfill his life dreams.”

That is what continues to drive Phillips in his work—remaining open to the possibilities, continuing to be a lifelong learner, and realizing his desire to help people and make a difference in the world around him. Thinking back to that advisor, the one who told him to keep asking questions, Phillips says, “I’m still that guy—when others say we ‘can’t,’ I want to understand and ask the question, ‘Why can’t we?’”