He could have been a mathematician. He could have been a linguist. Calvert Johnson ’71 was strong in these areas, enjoyed them, but he chose another path—music.

In a family living in Denver, Colorado, alongside five siblings, young Cal grew up in a home where music was considered a necessity and an achievement. Johnson’s father even made violins as a hobby. Even so, Johnson says, he was discouraged from taking a career path in music. Perhaps he could be an accountant? A linguist? Wouldn’t that be more…practical?

The teenager wasn’t afraid of following his own path. In high school, he excelled in math and he excelled in his classes in the Russian and Spanish languages. Eventually, he would become fluent in Spanish, French, German, and could get by in Italian—he even studied Arabic.

“It all comes from the same areas of the brain,” Johnson says. “I picked up the viola when my school orchestra needed a violist in 7th grade, and I’ve played the piano since 6th grade, the organ since 7th grade, the oboe in 10th grade. And I’ve always loved the pipe organ from church.”

When an admissions advisor from Kalamazoo College came through town during Johnson’s senior year in high school, Johnson’s attention sparked.

“The study abroad program got my attention,” he says. “I wanted a good liberal arts curriculum. And, I wanted to get far from home.”

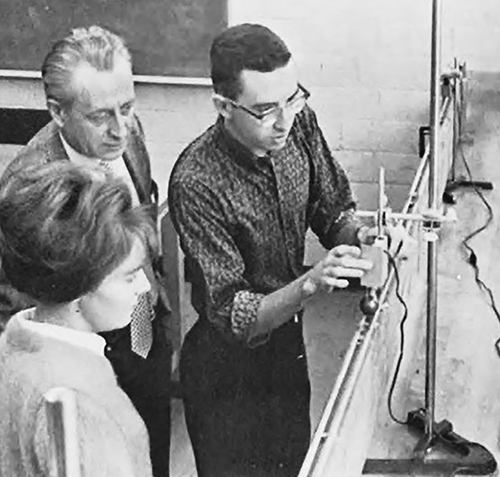

Exploring the world beyond held great appeal for Johnson, and he was up for the adventure. He stepped onto the Kalamazoo College campus for the first time in September 1967, a newly enrolled freshman, ready to embrace all that the College offered. While at first, he planned to major in foreign languages, by his junior year, he was focused fully on music.

“Once I could be persuaded that I could make a living with music, that I could teach at the college level and play the church organ, I was decided,” he says. “Taking those advanced calculus classes, I realized I wasn’t really interested in solving equations.”

Johnson had continued studying music throughout his years at K, focusing on keyboard instruments and participating in recitals and concerts, taking part in the Bach Festival. During his sophomore year, while still a math major, he was a mathematics teaching assistant in Honduras for his career service work, and the following year he studied abroad in Madrid, Spain. It was all he had hoped and more.

“I was in Central America for three months, and it was eye-opening,” Johnson says. “I was there all alone, and it forced me to rely on my Spanish skills. I heard the many dialects of the language, listening to others. That kind of exposure to another culture was enlightening.”

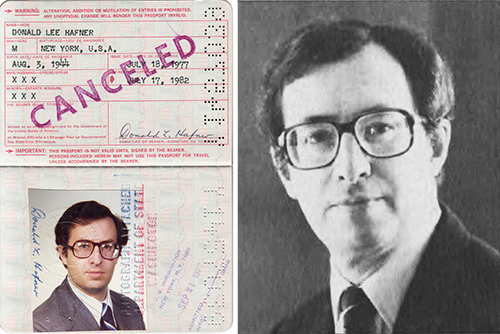

While in Madrid, Johnson took time to travel across Europe.

“My parents wrote a letter to the study abroad professors asking permission for me to travel alone,” Johnson says. “The trips were exhausting, figuring everything out in different languages and across different cultures, but it was all worth it.”

After earning his bachelor’s degree, magna cum laude, at K, Johnson continued his studies in organ and harpsichord at Northwestern University in Chicago, earning his master’s and then doctoral degrees in music. After receiving his degrees, he was awarded a Fulbright Fellowship to study organ music at the Toulouse Conservatoire in France.

“And then I got my first job as a choir director and organist at a church in South Arkansas,” Johnson says. “That was the biggest culture shock of all of my travels. There were railroad tracks through town that literally divided Black and white. On one side lived the millionaires, many of whom were members of the church, and on the other side lived the Black community. I spent two years there and was desperate to get out.”

It was an awakening to a deeper understanding of the marginalized that would remain with Johnson ever after. His next position, as associate professor of music, took him to Northeastern State University, in the Cherokee capitol Tahlequah, Oklahoma. For the next nine years, he became more acquainted with Native American culture, even as he longed to join a larger liberal arts institution.

That proved to be Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Georgia, where Johnson taught courses in sacred music, women in music, and music before 1750, as well as giving organ and harpsichord lessons.

“I was back at a liberal arts college, and it was wonderful to be back,” Johnson says.

When Johnson joined the faculty of Agnes Scott, the college was struggling to attract Black students, Johnson says.

“The president wanted me to help build community,” he says. “We had weekly convocations, and I looked for relevant music. When we had a Black Awareness week, I looked for music by Black composers, but found little. Students asked me for music by a Black woman, but it was only two days before the convocation, too late to find and prepare music, so I made a promise to find something for the next year.”

Johnson kept his word. When Sharon J. Willis, a Black composer and singer, founder of the Americolor Opera Alliance, was invited to speak at Agnes Scott, Johnson made a vital connection.

“She performed music by Florence Price, and I thought, there it is, right in my lap, what I was looking for,” Johnson says. “I cornered her afterwards to ask where I could get more of this music. It was dynamite! People needed to hear this.”

Determined to not only introduce the music of Black women to his students, Johnson took on the mission of bringing to light the music of marginalized composers to ever wider audiences.

“After all, we might be overlooking the very best around,” he says. “Why wouldn’t we want to find them and hear them? We can continue to play Handel and Bach, but why not play these, too? I have found over the years that audiences respond with great enthusiasm.”

Johnson researched the works of many such marginalized composers, but he took a special interest in the work of Florence Price (1887-1953), the first Black woman to have her work performed by a major American orchestra when the Chicago Symphony performed her “Symphony in E Minor” in 1933 at a concert titled, The Negro in Music. After that performance, however, her work had once again slipped into oblivion. Music composed by women was often not taken seriously, and that of a Black woman—even less so.

“I performed the music of Price at the next convocation, in 1988, playing her entire ‘Suite No. One,’” Johnson says.

In 1992, Johnson was on the steering committee for the American Guild of Organists convention in Atlanta, and he was struck by the realization that the national convention had not performed a single composition by a Black composer or a Black organist in 12 years.

“I think we can do something about that,” he told committee members. “When you think of Atlanta, you think of Martin Luther King and civil rights, and we also have a large Hispanic population that was underrepresented. I made it a theme for the convention, to represent the music of the Black and Hispanic communities and by women composers.”

“I cornered her afterwards to ask where I could get more of this music. It was dynamite! People needed to hear this.”

Johnson reached out to schools nationwide for recommendations. He invited musicians worldwide to submit recital proposals that included works by women, Blacks and Hispanics.

“Was there pushback? Was there ever!” Johnson chuckles. “They were furious. You can’t request proposals from distinguished performers, I was told. No one will come to this convention, they warned me.”

But they came. They came in droves. Given a venue that seated 2,000, Johnson filled almost every seat and felt vindicated as waves of applause greeted performances.

The positive reception only fueled Johnson’s interest in marginalized music more. He discovered the forgotten works of Asian women composers, tracked down their harpsichord and organ music and began to perform it. He gathered the music of Korean composers and added it to his repertoire, teaching students, publishing their manuscripts, but also performing at concerts and making recordings.

“I traveled to Oaxaca, Mexico, and found colonial-era music manuscripts that were stitched together by twine, the earliest Mexican organ music,” he says. “These were notebooks passed down through generations.”

Johnson’s interest in the work of Florence Price, however, remained a top focus as he collected manuscripts of her work, finding yet undiscovered compositions.

“I’ve just edited and published a fifth volume of a collection of Price’s work,” Johnson says. “And I am still sleuthing to be sure I have found them all.”

Johnson says he is fascinated by the story of Price, her commitment to her music from childhood on, even as her mother encouraged her to conceal her race, listing her on recital programs as Mexican to avoid the prejudices of her time. Price became a pianist, an organist, a composer, a music teacher, and earned critical acclaim in later years, even as performances of her work were few. She composed for orchestra, chamber music, choral music, solo pieces, symphonies and concertos.

“Florence Price has finally been welcomed into the canon of classical music,” Johnson says. “Today most major orchestras are performing and recording her symphonies, concertos and other symphonic works. Pianists and singers have been performing her solo vocal repertoire—think Marian Anderson and Leontyne Price, among others. Also, in the organ world, major organ departments are having their students study her works, and professors are performing them around the world.”

Johnson retired from Agnes Scott College in 2012, at which time he was the chair of the music department and the Charles A. Dana Professor of Music and college organist. He had served as chair of the faculty executive council, faculty representative on the college’s Board committees on finance and investment, and co-chaired the mission statement task force with the president of the college. He also was responsible for a conference on “Women in the Chicago Renaissance” that featured not only Florence Price but also Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks and choreographer Katherine Dunham.

Johnson now lives in Big Canoe, a mountain community and Audubon sanctuary an hour north of Atlanta, Georgia, with his spouse, Ken. He is anything but retired! Here he founded the Knowledge Series that features speakers, discussion groups and international events. He was a co-founder of the Black Bear Project to raise awareness of living in harmony with wildlife in the north Georgia mountains, and stepped up to become chair of the Conservation Committee. Musically, he is completing 16 years as organist at First Presbyterian Church in Marietta, Georgia, and is executive director of a chamber music series in the county: Casual Classics Concert Series. He is also on the Board of Directors of the North Georgia Community Foundation.

Even in his retirement, Johnson has not forgotten his own roots. He recently established the Calvert Johnson ’71 Endowment for the Maintenance of Keyboard Musical Instruments at Kalamazoo College. The endowment supports the upkeep of pianos, pipe organs, harpsichords and fortepianos in buildings across campus.

Johnson says, “My passion for music and keyboard instruments will always remain a part of my life, and that all came together at Kalamazoo College.”![]()