Nicholas Gann ’12 graduated from Kalamazoo College in the wreckage of the Great Recession. With his B.A. in political science, Gann would have loved to have gone on to D.C. to start his career. Yet coming from a middle-class family with two parents who were teachers, there was no way he could manage an unpaid internship there, which is the route most folks take.

“In our family, we say there’s no shame in paying your bills on time, so I did all sorts of odd jobs after college, stringing paychecks together,” Gann said. “I substitute taught in Detroit. I sold cars. I kept thinking I was going to save some money and then I’d know when an opportunity presented itself.”

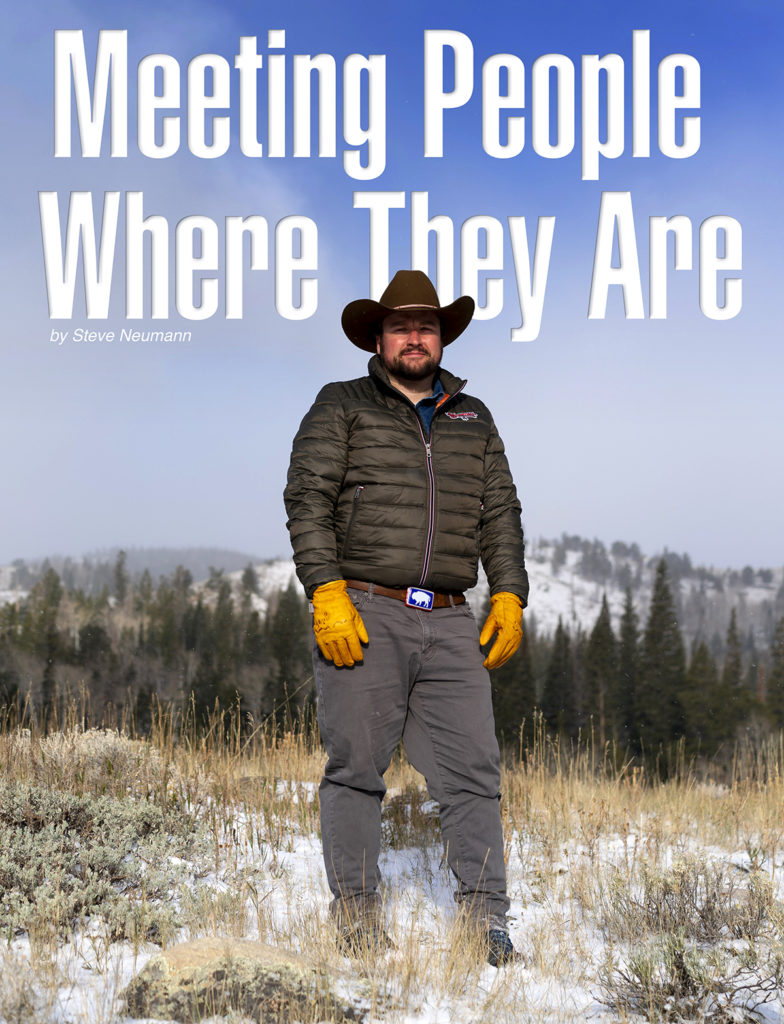

Fortunately, opportunities would eventually present themselves to Gann that would take him from the forests of Northern Michigan to the big sky of Montana, then to blustery Chicago, and finally back west to the Grand Tetons of Wyoming—where he’s been the Strategic Partnerships Manager for the Wyoming Office of Tourism since October 2019.

All along Gann’s serpentine career path, he credits his liberal arts education from K for being able to learn as much about himself as he did about other people, by being open to different experiences, learning about the context of people’s situations and thinking critically.

“That trajectory of promoting curiosity, independent thought, and meeting people where they are was started by my parents, grew at K, and developed from there,” Gann said.

Gann’s parents were teachers who lived and worked overseas for nearly 15 years—in countries ranging from Belgium, United Kingdom, Denmark, Turkey, West Germany, the Soviet Union, Nepal and Pakistan—before settling down in Northern Michigan. Their household was filled with books and conversations and questions.

“They would have these pretty incredible stories,” Gann said. “They had an inherent curiosity about how people do things, about different cultures and religions. I think when you grow up in a household like that, you also develop this sort of curious mind.”

In high school, that curiosity inspired Gann to study abroad for a year in Germany, an experience he cherished, and one that led him to K.

“When it was time to start looking at colleges, K’s study abroad program was a natural fit for me,” Gann said.

Gann’s six-month study abroad at K would also bring him back to Germany, to the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg in Bavaria. This time the program required him to do an internship that showed some cultural relevance, so he stuck with his roots in bucolic Northern Michigan.

“I actually did my internship with the Bavarian Forestry Service, which was pretty wild,” Gann said. “I’d be out hunting or planting trees with my supervisor in the morning, and then get dropped off at class kind of sweaty and covered in dirt wearing my red long johns, wool pants and suspenders—much to the curiosity of order-driven Germans.”

In addition to being able to both pursue his studies and indulge in his favorite childhood pastimes, Gann also had a great time there with his first roommate at K, Nathan Gilmour ’12.

“We met each other on study abroad in high school, and then we just kept in contact,” Gann said. “Nathan applied to Kalamazoo College, too; we decided to be roommates freshman year and then we went back to Germany together.”

Gann’s internship with the Bavarian Forestry Service was in the back of his mind when, after about a year of doing odd jobs, another friend of his from K, Zach Holden ’12, told him about an internship he was doing in Montana for Project Vote Smart (now Vote Smart), a non-profit, non-partisan research organization that collects and distributes information on candidates for public office in the United States.

“It was this big 150-acre ranch in the middle of nowhere on the Continental Divide,” Gann said. “I love the outdoors, so I used the savings from all my odd jobs to do that internship, and then I got hired full time thereafter.”

After a couple of years with Vote Smart, Gann started proactively thinking about his next step. As he was exploring the job market, his father, who was a principal at the time, put Gann in touch with one of the parent chaperones he met on a field trip in Washington, D.C., who was from Chicago.

“He said he could help me get my foot in the door for an internship in Chicago with ASGK Public Strategies, now Kivvit. Current owner and fellow Michigander, Eric Sedler, partnered with David Axelrod to found the firm and gave me my first chance at a career. I’ll always be very grateful to Eric for that opportunity to prove myself,” Gann said.

Gann applied, but the process took some time. While he was waiting to hear back from Kivvit, he went back to Michigan and began working as a roofer.

“One day I was carrying a bunch of shingles up a roof, and I got this call where I was offered the internship on a three-month contract,” Gann said. “I ended up being there for five years, working on a lot of really interesting stuff with a lot of really smart, passionate people.”

One of Gann’s highlights at Kivvit was working on a variety of projects for the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee. Gann helped put together communications plans and assisted with media training for athletes.

“I also worked with the Navy SEAL Foundation to generate media coverage around their Chicago Evening of Tribute event, which featured retired four-star Army General and former CIA Director David Petraeus,” Gann said.

His responsibilities on that project included drafting press releases, staffing interviews with former SEALs like Rear Admiral Garry Bonelli and Mike Day, and working with the media at the event itself.

Other highlights at Kivvit included promoting the 2016 Louis Vuitton America’s Cup World Series Chicago, staffing events for the Obama Foundation and having a small role on the campaign to bring the Obama Presidential Center to Chicago.

Though Gann enjoyed living and working in Chicago, he had grown up exploring the forests, lakes and rivers of Northern Michigan, and he longed to get back to those kinds of environs. So when he discovered a job posting for a Strategic Partnerships Manager for the Wyoming Office of Tourism, he jumped at the chance.

“It’s pretty hard to turn down a job when they’re gonna pay you to go to Yellowstone,” Gann said. “Plus, the job blended the public affairs experience I could bring with work in the government arena, and also allowed me to help oversee the state’s professional rodeo team, Team Wyoming, and support college rodeo programs and the sport as whole across the state.”

Some of the main things that attracted Gann to the role were the community building and economic development aspects, which provided him with yet another opportunity to be exposed to different perspectives and contexts.

“I really enjoy helping communities figure out strategic and economic development plans, because you get people who are passionate about their communities,” Gann said. “Leaning on my previous experience living in an 800-person town in Montana, I understood the dynamic there.”

However, just like the Great Recession when Gann graduated from K, the COVID-19 pandemic threw a very large wrench in the works.

“Tourism is the second largest industry in Wyoming,” Gann said. “All of a sudden, borders are closed and you’re not getting that international visitation from Asia or Canada or Europe going to Yellowstone and injecting money into the country’s least-populated state.”

In response, Gann recruited more than 10 other government agencies like the National Park Service, the U.S. Forest Service and other Wyoming agencies, to join his agency’s responsible recreation campaign called “WY Responsibly.”

“We had to take a step back as an agency and retool our campaign on the fly,” Gann said. “We had to rethink how we were going to approach the pandemic, what we were going to focus on and, most importantly, how to do this safely.”

While many people may think of tourism in Wyoming as a family driving through Yellowstone taking pictures, there’s a lot more to the Cowboy State.

“Wyoming is a heavy exporter of extraction minerals,” Gann said. “So anytime the industry fluctuates—whether it’s coal, trona or uranium—all those hotel rooms for miners that companies pay for are gone. And by extension, there’s things like lost restaurant revenue, lodging revenue and other local tax revenues that hurt these communities.”

While Wyoming, like every other state in the nation, did experience some losses, the state as a whole fared much better than others. In 2020, Wyoming had record monthly visitation rates in its national parks, and a 300 percent increase in visitation at some state parks. Additionally, initial economic indicators from last year show that while the U.S. travel industry contracted by about 36 percent on average, Wyoming only contracted by 23 percent.

“We were able to keep money coming in and help sustain our communities,” Gann said. “We applied for CARES Act and then American Rescue Plan funding to serve as a funnel for these communities, applying on the behalf of the State then distributing it out to them.”

Next year is the 150th anniversary of Yellowstone, and Gann expects it to be a post-COVID boon to the state.

“Our goal next year is to focus on economic development and destination development across the state, county by county, continuing to help communities with their strategic development plans, so we can keep building on this momentum,” Gann said.

As Gann looks forward to working toward a brighter future for the businesses and communities of Wyoming in a hopefully COVID-free world, he never forgets how he got here, or how many different perspectives and cultures he’s encountered along the way.

“I’ve worked and lived in some incredibly conservative and liberal areas,” Gann said. “I’ve been successful by remembering that everybody—whether a rancher in Wyoming or a family on the South Side of Chicago—has a story and is proud of where they come from, so being curious is the best way to understand how they got to their point of view.

“At K, learning to take a step back and be curious has served me well and taught me to meet people where they are, and that’s opened a lot of doors for me.”![]()